What is Krabbe Disease?:

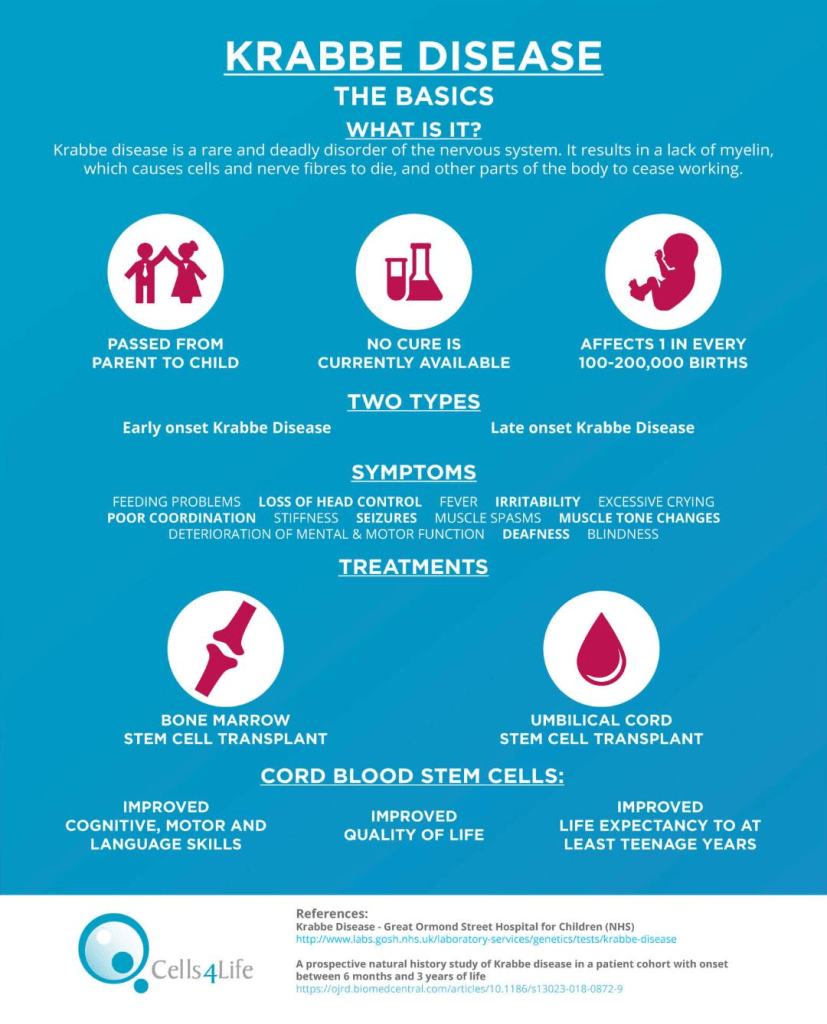

Krabbe disease is a specific sub-type of Leukodystrophy that affects the brain’s white matter. Additionally, Krabbe disease is considered an orphan disease. This means that it is a rare disease that receives little to no funding or research for treatments, typically due to a tiny population of cases, as well as the fact that it costs so much to develop treatment. A person with Krabbe disease has a galactocerebrosidase (GALC) enzyme deficiency, which breaks down specific lipids. The failure to break down these lipids due to Krabbe disease causes the deterioration of the myelin sheath that surrounds the nerves in the brain in a process called demyelination. As a result of demyelination, globular fat cells build in the affected areas of the brain. Krabbe disease is also known to have four different subsets based on the age of onset. These ages include early infantile-onset, which occurs in children under 13 months old; late-infantile onset, which occurs in children between the ages of 13 and 36 months; adolescent-onset, and adult-onset. The likelihood of a person being diagnosed with Krabbe disease post-infancy is exceptionally uncommon, as 85% of all cases of Krabbe disease are within the infantile-onset bracket.

Symptoms:

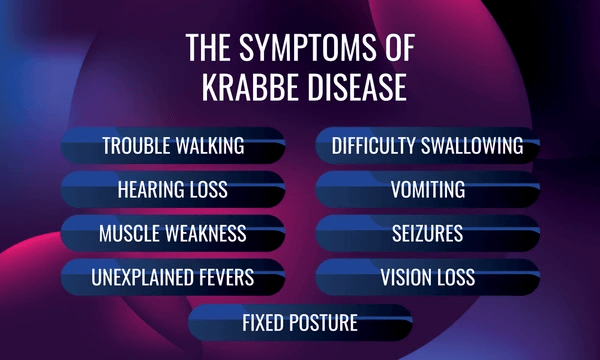

The particular symptoms of any specific Krabbe disease case vary, especially between the different age groups. Patients with Krabbe disease begin developing normally, which is unfortunately followed by increasingly rapid and severe neurological deterioration. In particular, people with infantile-onset Krabbe disease experience symptoms such as excessive crying, unexplained fevers, difficulty feeding, loss of head control, hypersensitivity (to noise specifically), poor weight gain, and spasticity of the lower extremities. The symptoms of later-onset Krabbe disease are noticeably different from those experienced in cases of infantile-onset Krabbe disease. These symptoms experienced later in life include delayed development, loss of motor function, seizures, spasticity, vision issues, and a burning pain in the person’s extremities. The most striking symptom, however, is likely the regression of previously acquired skills. Other possible symptoms may include dysphagia and peripheral neuropathy.

Causes:

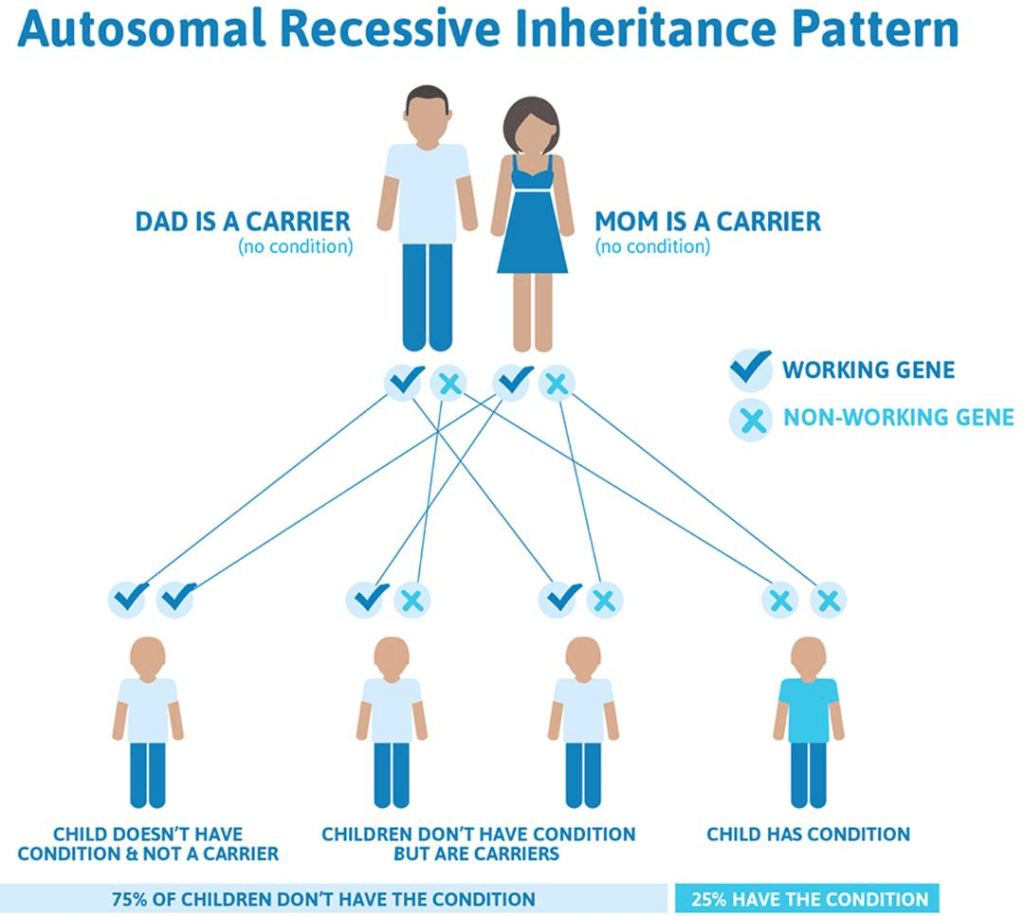

Krabbe disease is classified as an “autosomal recessive genetic disorder” caused by the pathogenic variations in the GALC gene. This gene causes a deficiency in the enzyme galactosylceramidase, which is another name for the enzyme galactocerebrosidase. This enzyme creates the key component of the myelin sheath: galactosylceramide. Galactosylceramide is vital to the degradation of old, worn membranes in the brain and the creation of healthy brain membranes. Thus, when there is a severe deficiency of the GALC gene, it makes way for a buildup of the lipids the enzyme should have been destroying. This excess of galactolipids is toxic to the cells, forming the protective myelin sheath around the brain’s nerve cells. Without a myelin sheath to enable the transmission of nerve impulses, loss of neurological function ensues.

In addition to catalyzing the creation and degradation of myelin sheaths, GALC also catalyzes the breakdown of psychosine, a highly toxic lipid byproduct made during myelin formation. When psychosine inevitably accumulates without any enzyme to break it down, it further degrades the myelin wall, which is no longer able to replenish itself.

Krabbe disease is considered to be a recessive genetic disorder. This means it occurs when a child disease-carrying genes from each parent. An individual with the gene would have received one recessive gene from each parent. If a person receives one normal gene and one gene that carries the disease, then the person will be a carrier for the disease, but they will not experience any symptoms. If the child receives two normal genes from their parents, they will not be a carrier or have the disease. With each pregnancy between two carriers, there is a 25% chance the child will have the disease, a 50% chance the child will be a carrier like the parents and a 25% chance the child will not have the disease and won’t be a carrier. It should also be noted that the GALC gene is not sex-bound, meaning that the risk of contracting the disease is the same for both males and females.

Many different specific mutations in the GALC gene cause infantile Krabbe disease. The only similarity between some of these mutations is that they severely limit the GALC activity. Some variations in the gene can cause a very mild form of Krabbe disease.

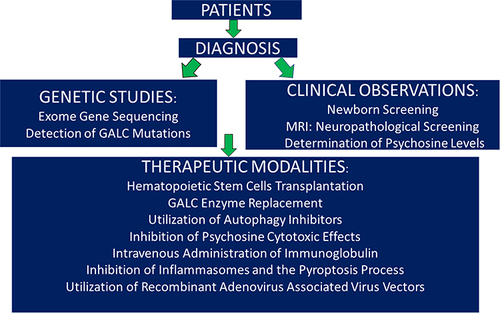

Diagnosis:

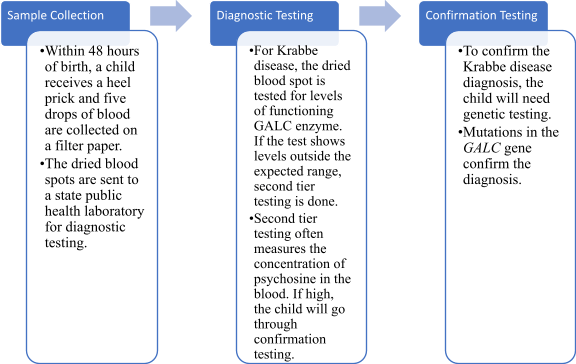

Krabbe disease can be easily diagnosed by testing the GALC enzyme’s activity, especially in white blood cells. This can be taken from blood samples, skin cells, or amniotic fluids. In certain places in the U.S., it is required to scan newborns for the disease. When newborns are screened, GALC is measured via a liquid chromatography test. Blood can also be taken from the baby if necessary. If any abnormal GALC readings come up, additional testing is to follow suit. This further testing typically includes the measurement of the psychosine concentration. Occasionally, the testing consists of a sequence analysis of the GALC gene. The most common mutation of the GALC gene is the GALC 30-kb deletion. The measurement of the psychosine concentration is often more accurate than the GALC activity, considering that there are many mutations to the GALC gene that are harmless or not disease-causing. Elevated psychosine levels are those any higher than 10 nmol/L, which would support the diagnosis of infantile Krabbe disease. If the levels are less than 2 nmol/L, it would be safe to assume that that individual does not have the disease. Any value between those would support the diagnosis of later-onset Krabbe disease in that individual.

In-utero testing is also available for particularly high-risk couples, which can lead to pre-birth diagnosis. This aids in quick intervention and a higher likelihood of successful treatment. If Krabbe disease is suspected in a patient, a neurological assessment and regular genetic testing are typically performed. These tests usually include an MRI, an EEG, and a lumbar puncture to collect cerebrospinal fluid. The reason this fluid must be collected is because an increase in spinal fluid is standard in babies with infantile Krabbe disease. The MRI, however, is most beneficial in assessing the disease’s progression and how effective the treatment is. The EEG helps to show signs of abnormal brain waves.

Treatment:

The current treatment for Krabbe disease is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, also known as HSCT. These stem cells are typically transferred from the bone marrow or the umbilical cord. However, the people who benefit the most from this transplantation are those asymptomatic individuals (individuals who experience normal development, aside from some motor delays). The results of this treatment in symptomatic cases vary from person to person as it differs based on age and severity of symptoms. HSCT is not recommended for symptomatic persons, but its effectiveness is monitored via a measurement of psychosine concentration. This works because psychosine concentration should decrease over time if the therapy proves successful. Unfortunately, HSCT cannot reverse the damage done by the disease already, even if the treatment is used with presymptomatic patients.

For symptomatic patients where HSCT is not recommended, treatment is symptom-based and designed to support patients. Patients in this bracket may have to undergo regular examinations to help their doctors track the progression of their patient’s disease. This will inevitably help them to determine the best symptomatic treatment approach. Due to the numerous symptoms experienced by those with Krabbe disease, many specialists may be needed to decide the course of treatment. It is recommended for those with Krabbe disease not to take antipsychotics, multiple seizure medications, or any essential childhood vaccines, as it is highly likely they will cause rapid disease progression and neurological degeneration.

Quality of Life:

Unfortunately, the average lifespan after symptoms begin is only two years, but it can range from eight months to nine years; this is specific to infantile-onset Krabbe disease. Later-onset Krabbe disease has a slower neurological function decline, resulting in an increased life expectancy. It averages out to eight years after symptoms begin. Adults diagnosed with Krabbe disease are many times more likely to have significant neurological impairments than those diagnosed in infancy, but, contrastingly, they could very well live 30-50 years after their diagnosis, on average. Furthermore, the protective myelin sheath surrounding the brain’s nerves is negatively impacted due to excess galactolipids. This often progresses to cause life-threatening complications, which can be the biggest threat to people with Krabbe disease.

How You Can Make a Difference:

Progress on improved treatment for Krabbe disease is deeply inhibited by the lack of support and funding, simply based on the low number of cases. Clinical trials and other studies cannot happen without the necessary funding. If you are able, please donate here! If you are unable to donate to Krabbe disease research, consider volunteering your time to raise awareness for this orphan disease. To learn more about Krabbe disease, fundraising opportunities, or the progress being made on treatment, visit KrabbeConnect! KrabbeConnect is an organization that strives to eradicate Krabbe disease through patient advocacy, clinical trials, and more! Affiliated with the National Organization for Rare Disorders, KrabbeConnect is patient-oriented and engages in pioneering research toward a cure for Krabbe disease.

Let’s keep spreading awareness! – Lily

References:

Wenger, D. (2024, March 13). Krabbe Disease – Symptoms, Causes, Treatment. NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/leukodystrophy-krabbes/

Leave a comment