What is aHUS?:

aHUS is an orphan disease characterized by a very low count of red blood cells circulating in the body as a result of their own destruction. This destruction of red blood cells is called hemolytic anemia. With aHUS, an individual will also have a low platelet count, since they are being consumed, as well as the individual’s kidneys will typically be unable to separate waste products from the blood and into the urine, which is a condition called uremia.

This disease is far different from typical hemolytic uremic syndrome, which is typically a food-borne disease caused by the production of the E. coli virus by Shiga toxins in the body. aHUS is known to be a genetic disease, but there have been some cases thought to be caused by autoantibodies, however, some cases have been caused by unknown reasons, so there is still much more to be researched. It is typical to see aHUS become a chronic disorder with patients having multiple episodes, contrastingly, those with typical HUS see much improvement after treatment following a severe, life-threatening episode. Since aHUS can become chronic, there are several chronic symptoms associated with the disease. These conditions typically include high blood pressure and, potentially kidney failure. The most characteristic symptom of aHUS is the formation of blood clots in the small blood vessels of the body, blocking blood flow, especially to the kidneys.

Symptoms:

aHUS symptoms can start developing before birth up until adulthood. In childhoods the disease is usually onset after an infection, typically these infections are severe infections of the upper respiratory tract or gastroenteritis, which is often confused with the other type of hemolytic uremic syndrome: Stx HUS. This is because gastroenteritis is nearly always preceded by an episode of diarrhea. This may not always be the case, however, because the disease has many different causes, so it may manifest itself differently on a case by case basis.

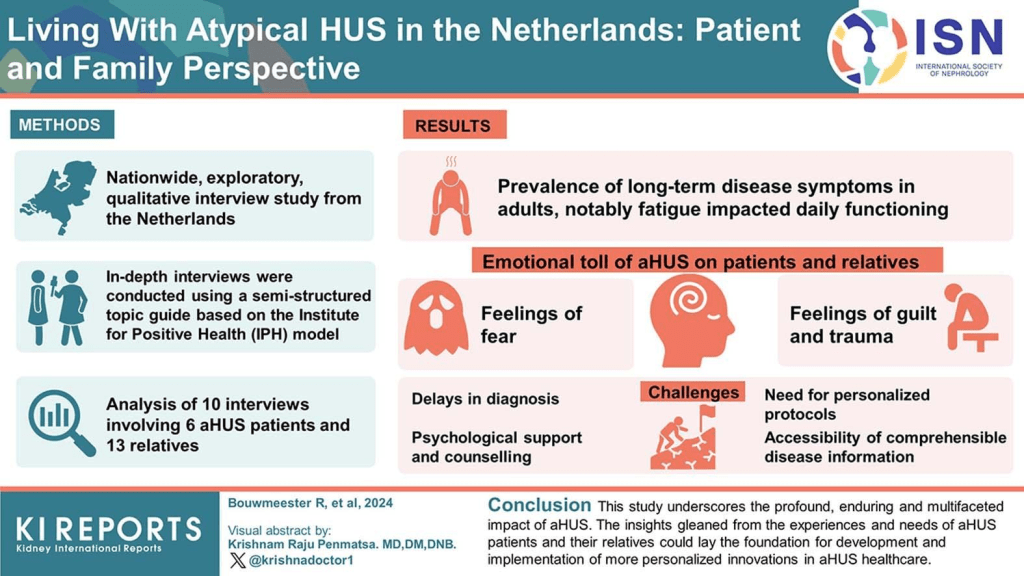

In the early stages of aHUS development, individuals feel the general symptoms of an illness, fatigue, lethargy, and irritability. However, even though these early symptoms are rather vague, it is very important to get aHUS diagnosed during this stage, considering that the disease is progressive and the symptoms only get worse following this stage. The main signs of aHUS are hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute kidney failure. Hemolytic anemia is when red blood cells are prematurely destroyed, leaving the body with an inappropriate amount of red blood cells. Thrombocytopenia occurs when there is a low level of platelets in the body, which is the cell responsible for causing blood clots. Thus, the consumption and thereby lack of platelets causes the platelets to ‘stick’ together and cause small blood clots throughout the body, impairing blood flow.

The kidney disease itself can be mild or severe, but it is common for the condition of the kidneys to worsen after each episode. Blood proteins and/or blood itself in the urine is common, especially during acute episodes. Since it is progressive, this can eventually lead to full-on renal failure, requiring regular dialysis or a kidney transplant. Kidney disease can cause high blood pressure due to the lack of blood flow in the body as a result of the amount of small blood clots. The high blood pressure may get severe enough to cause intense headaches and potentially seizures.

These blood clots can also form in blood vessels responsible for transporting blood to different organs, aside from just the kidney. Thus, it is possible for an aHUS patient to have other organs fail in addition to or instead of their kidneys. The brain, gastrointestinal tract, liver, lungs, and heart could be impaired by the blood clots, however, the specific symptoms associated with each patient vary based on which organ is being affected. Specifically if the cardiovascular system is affected, heart attacks or heart disease could occur. If the nervous system is impacted, headaches, double vision, irritability, drowsiness, paralysis of the face, seizures, stroke, and coma could all be potential symptoms. If the lungs are affected, bleeding and/or fluid accumulation in the lungs could also occur.

Causes:

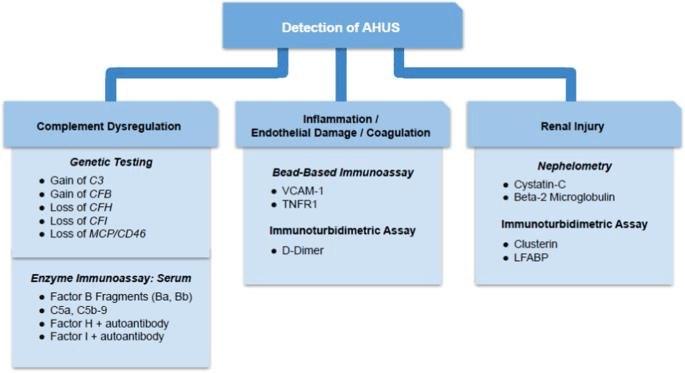

aHUS is typically associated with the mutation of the gene responsible for encoding proteins involved in the complement system, a group of proteins that work to fight infection in the body. It is a part of the larger immune system. These complement proteins are responsible for fighting off bacteria and viruses in the body, making up a large multi-protein body that fights off infection. Other involved proteins help to regulate the formation of an attack complex, which exists to protect the body and its cells from any damage from opposing viruses.

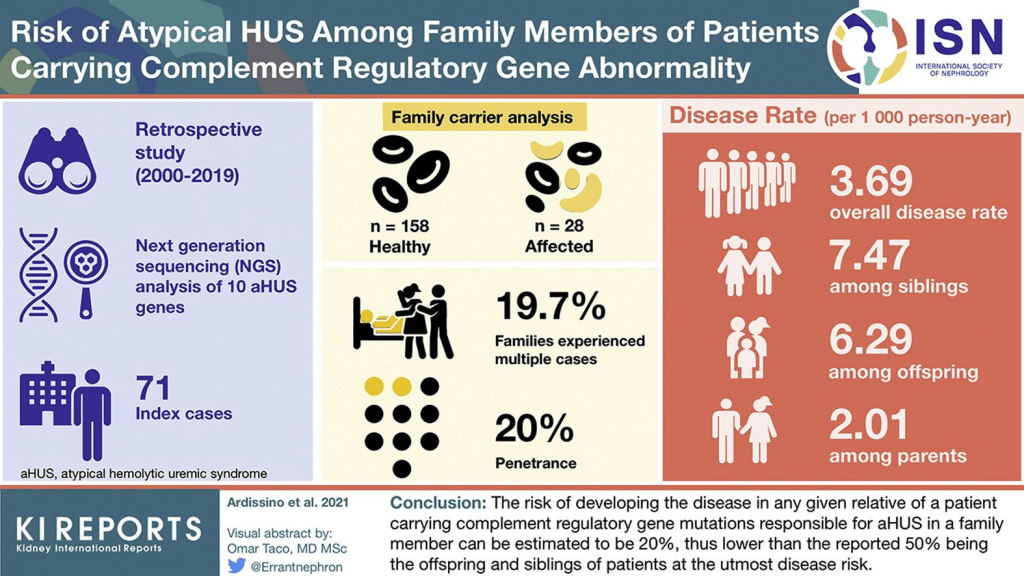

With aHUS, it is most common for people to have several mutated genes that are responsible for encoding regulatory proteins. A mutation in just one gene is not enough to cause aHUS, these genes likely have a genetic predisposition to contract aHUS, meaning that a person may have a gene that causes that disorder, but it must be triggered by a particular event or circumstance. This could be environmental or as a result of contracting a different illness.

Most often, the triggering disease is an acute infection, however, other triggers include chicken pox or influenza. With women the most common trigger is pregnancy. People with aHUS may have developed the disorder as a result of a mutation in a secondary gene or genetic variant. These could include single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which are the most populous variations and occur often in human DNA, however, normally, SNPs have no effect on the health of a person.

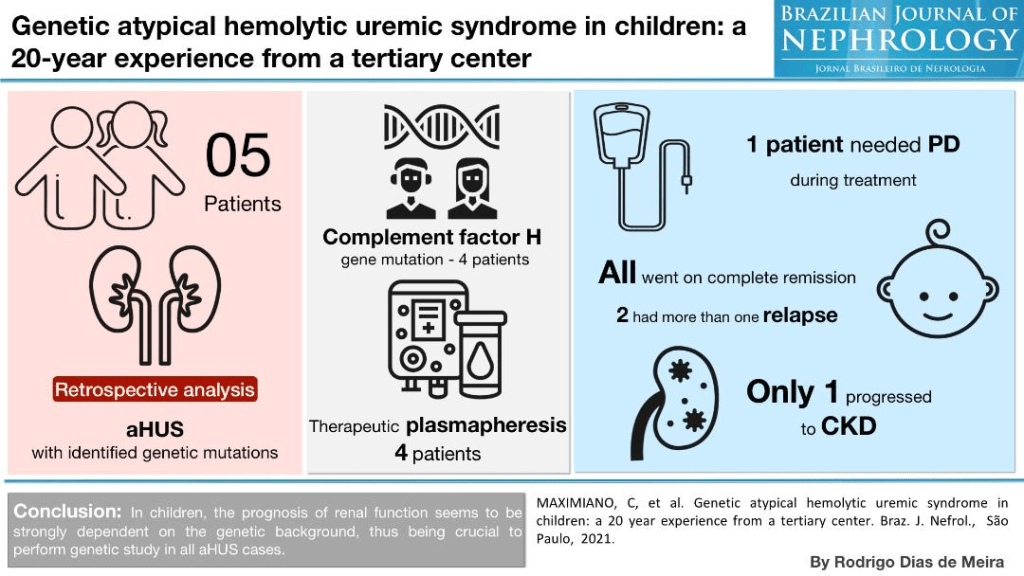

There are at least six genes thus far that have been directly linked with the development of aHUS. 30% of cases are the result of a mutation to the gene responsible for directing the production of a protein called factor H, a kind of regulatory protein in the complement system designed to protect the blood vessels. When this gene is mutated, causing the deficiency of factor H, the potential for damage to the blood vessels and kidneys is increased with secondary harm to red blood cells and platelets plausible. Other cases of aHUS are caused by mutations in different genes, which are responsible for coding different regulatory proteins. Mutations to the gene that encodes thrombomodulin (THBD), which is an anticoagulant glycoprotein known to also possess some regulatory properties are least often associated with aHUS. A seventh gene called DGKE is suspected by researchers to be linked to aHUS, however, it is thus far considered to be a distinct disorder. This is because the protein produced by DGKE is not a part of the complement system.

The specific mutated gene may have an effect with the particular symptoms associated with each individual case. This is a prime example of genotype-phenotype correlation. Thus, the treatment of each individual may be determined by the gene affected. Contrastingly, some people contract aHUS due to their autoantibodies destroying proteins that are made by the aforementioned complement system genes. It should be noted that autoantibodies are antibodies that attack healthy, not harmful tissues instead of foreign invaders. The reason behind the development of these autoantibodies is unknown and requires further study. There are some individuals (30%-50%) who have no presence of a mutated gene nor autoantibodies, these individuals are said to have idiopathic aHUS, but researchers suspect that they might just have unidentified gene mutations.

When genetic mutations occur in an individual they are random and sporadic, meaning it is not necessarily a familial history of the disorder (only about 20% of cases report genes having been inherited). In these cases, the disorder manifests as an autosomal dominant trait (affecting adults more), but it is also possible for it to be a recessive trait. If it is a dominant trait, the disease will still be contracted even if it is only inherited from one parent, or it can be caused by a new mutation or gene change in the offspring. The risk would be 50% for each pregnancy if a parent has the dominant gene, and the risk would be the same for male and female offspring. However, if the trait is recessive, the child must receive the trait from both parents to have the disorder. They will be a carrier if they receive one recessive and one normal gene, but will not have symptoms. Two carrier parents have a 25% risk to have a child with aHUS. The risk for a carrier child is 50%, and the risk for a child to receive both normal genes is 25%. All these percentages are the same for both male and female children.

Diagnosis:

The diagnosis process of aHUS is more complicated than other rare disorders, as it cannot be traced back through family lineage. The criteria associated with the diagnosis of aHUS include hemolytic anemia, low platelet count, and kidney dysfunction, as well as the potential dysfunction of other organs. aHUS can be considered genetic if family members develop the disorder at least 6 months apart, or if an aHUS-causing mutation is found on a suspected aHUS-associated gene. One difference between aHUS and Stx HUS is that patients with aHUS do not tend to experience persistent bloody diarrhea, characteristic of Stx HUS. However, up to 50% of children with aHUS may experience diarrhea. The main indications to kidney specialists that suggest a patient may have aHUS are the lack of bloody diarrhea, negative stool cultures E. coli, swelling from the accumulation of fluid, blood in the urine, high protein concentration in the urine, elevated blood pressure, and more.

Treatment:

Treatment is recommended to be undergone by a team of doctors who are familiar with the specific challenges associated with aHUS. These doctors could include pediatricians, kidney specialists, intensive care specialists, nurses, nutritionists, etc. In the beginning stages of treatments, maintaining proper nutrition and hydration is crucial. Blood and platelet transfusions may be necessary, though platelet transfusions are usually avoided. Blood vessel-expanding drugs are also commonly administered. Some individuals are diagnosed late, after kidney dysfunction already begun, so dialysis might be needed even early on.

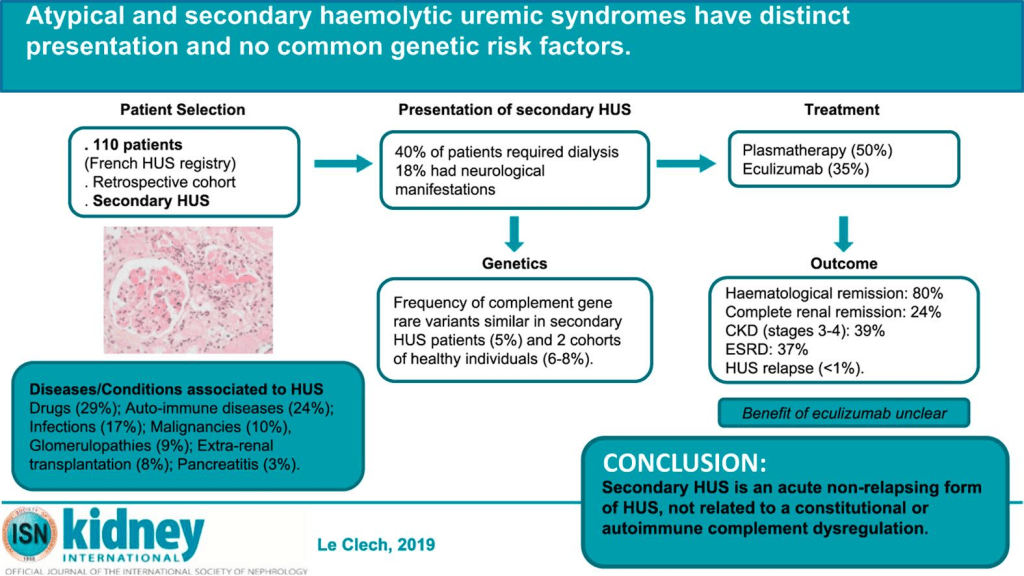

Plasma infusion was the standard treatment for aHUS for many years. This includes getting fresh plasma as well as having the harmful plasma products removed from the blood. This can help to eliminate mutated factors in the blood as well as get rid of any autoantibodies. Plasma therapy did prove successful, however, many patients relapsed when they did not receive long-term care. Other individuals saw improved state of any blood complications, but still experience kidney dysfunction to the point of kidney failure. Thus, plasma therapy has not been studied as a treatment for aHUS.

Those who experience severe kidney dysfunction and failure may need a kidney transplant, however, the procedure is highly controversial as approximately 50% of patients who have the operation have the disease reoccur in the new organ. Patients should undergo graft prognosis before transplantation to increase the odds of not developing the disease in their newly-grafted organ. However, further genetic testing should be done before a person considers live related donation to a family member to ensure they will not develop the disorder later in life.

Certain drugs are able to suppress the immune system, which can treat aHUS as it decreases the autoantibodies produced by factor H. The ideal treatment for those with a mutated DGKE gene has yet to be identified, so further studies must be done.

How You Can Make an Impact:

The ability to further the studies and research for treatments of the various kinds of aHUS is limited by the support for the orphan disease. Due to the small number of cases, people may go without proper care, as the funding for the rare disorder is minimal. If you can, please donate here! If you are unable to donate, consider volunteering your time by raising awareness for this rare disorder. If you’re interested in learning more about aHUS, donation opportunities, or the progress being made on new treatments, visit the aHUS Foundation! The aHUS Foundation strives to provide everyone affected by or interested in aHUS the most up to date information, a supportive network of healthcare providers and families, and collaborative opportunities via conferences. Their ultimate goal is to spread awareness for aHUS!

Let’s keep spreading awareness! – Lily

References:

Lieberman, K. (2024, May 29). Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome – Symptoms, Causes, Treatment | NORD. NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders); NORD. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/atypical-hemolytic-uremic-syndrome/

Leave a comment