What is Dravet Syndrome?:

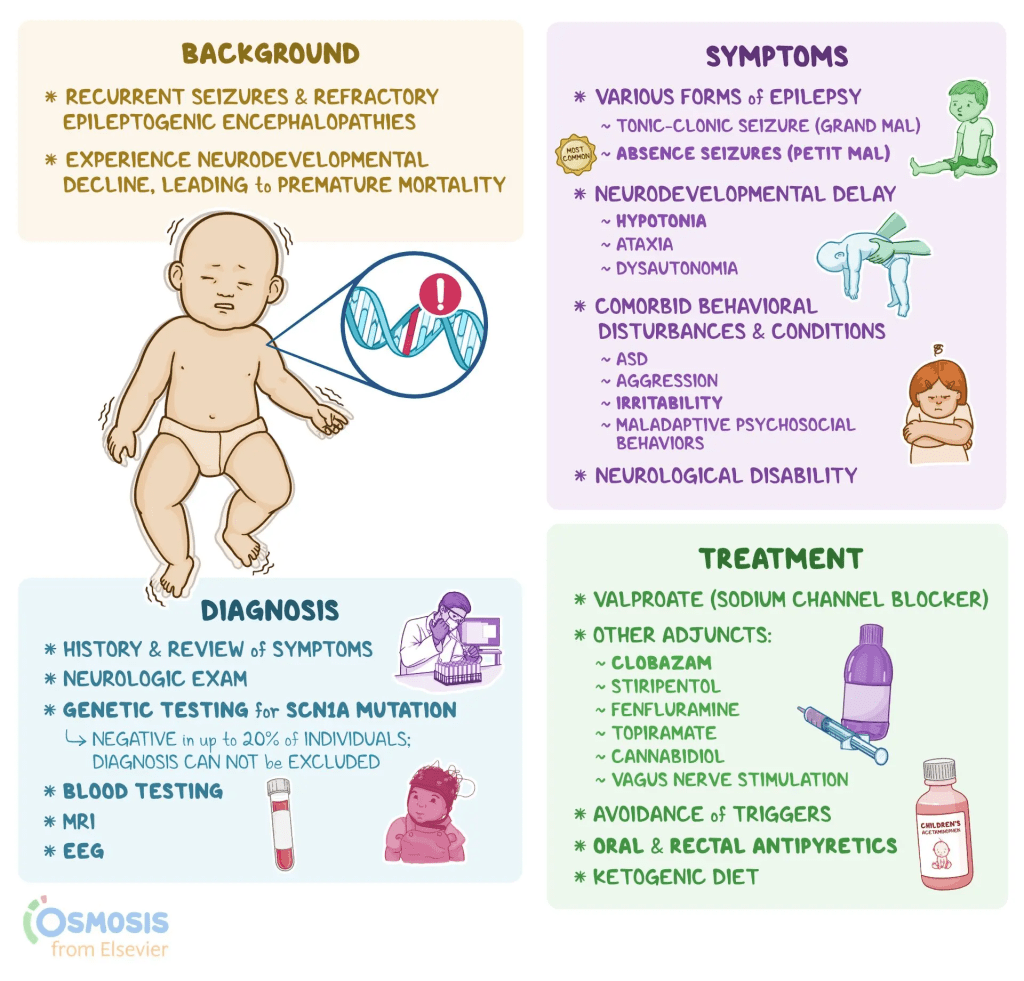

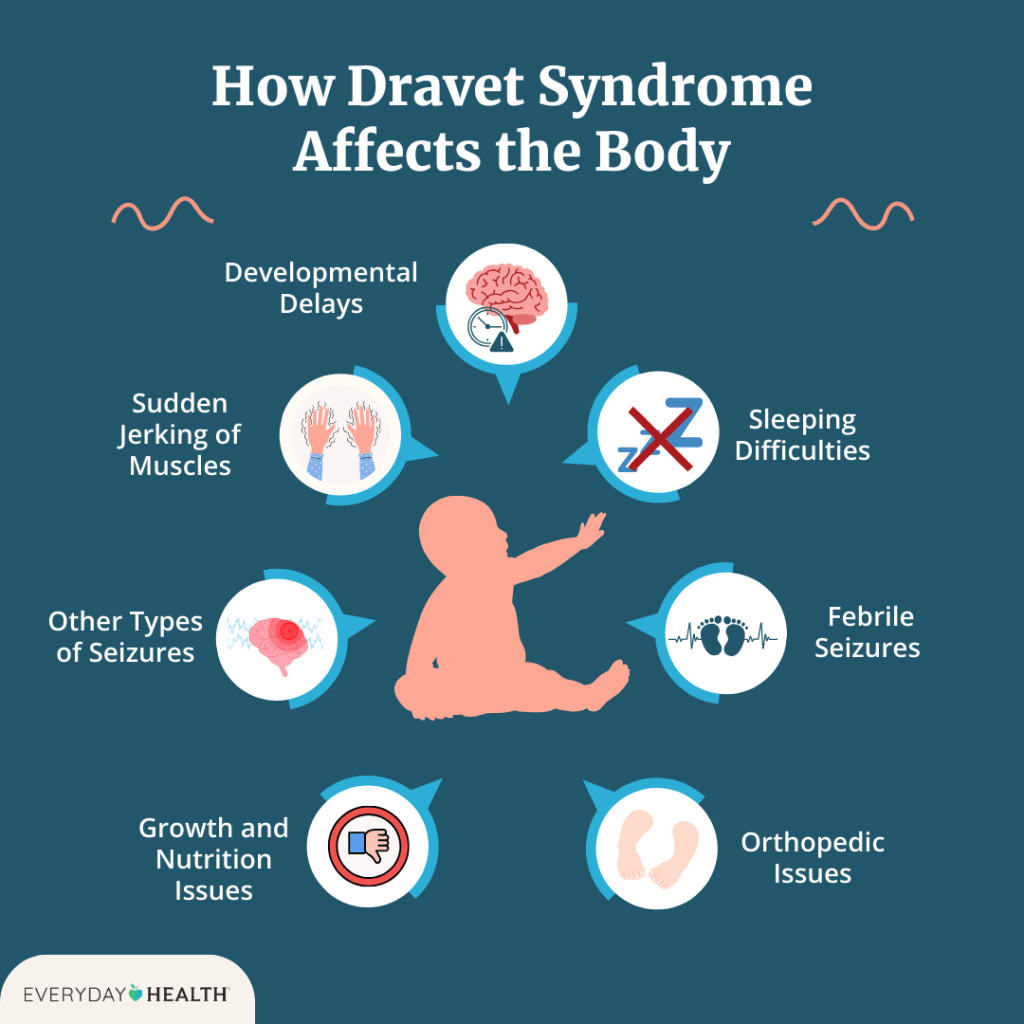

Dravet syndrome is a rare but severe type of epilepsy that typically starts within the first year of life in infants who previously seemed healthy. It is marked by frequent, long-lasting seizures, often triggered by fevers or high body temperature. Over time, individuals with DS may develop a range of neurological and developmental challenges, including delayed development, difficulty with speech, coordination problems, low muscle tone, behavioral issues, and disrupted sleep. Other symptoms can include problems with growth, nutrition, and regulation of body functions like temperature and sweating due to dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system.

The condition is classified as both an epileptic encephalopathy—meaning the seizures themselves cause brain dysfunction—and a channelopathy, because it’s often linked to mutations in genes that affect sodium channels in nerve cells. These channels are essential for proper communication between neurons. Around 80% of individuals with DS have a mutation in the SCN1A gene, though not all such mutations result in DS. Early in the disease, EEG scans and brain imaging may appear normal, but abnormalities and developmental delays typically become evident by the second or third year of life. Most people with DS will eventually need lifelong support.

Seizures in DS can take various forms—such as tonic-clonic, myoclonic, or atypical absence seizures—and are often prolonged, sometimes lasting over 30 minutes in a condition known as status epilepticus, which can be life-threatening and demands immediate medical care. As children grow older, mobility and speech may worsen, and therapies like physical, speech, and occupational therapy are commonly recommended.

Dravet syndrome is associated with a significantly increased risk of death, with mortality rates estimated at 15% to 20% by adulthood. The leading causes of death include sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), especially during sleep, and complications from prolonged seizures. Certain anti-seizure medications—such as carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, vigabatrin, and daily use of phenytoin—are typically avoided, as they can worsen seizures in individuals with DS.

Symptoms:

Seizures in DS typically begin in infancy, with the average age of onset around 5.2 months, most commonly occurring before a child turns one. The first seizure is often prolonged and may present as either a generalized tonic-clonic or hemiclonic seizure, sometimes accompanied by fever, though not always. While shorter seizures can also happen early on, hyperthermia—caused by fevers, hot baths, physical activity, or warm environments—is a frequent trigger due to the patient’s heightened sensitivity to temperature increases.

As the child grows, additional types of seizures may develop. Myoclonic seizures often appear by age two, but their presence isn’t necessary for diagnosis. Seizure types like non-convulsive status epilepticus, focal seizures with impaired awareness, and atypical absence seizures tend to show up after age two. On the other hand, typical absence seizures and epileptic spasms are rare in DS. Early diagnostic tools like EEGs, MRIs, and spinal taps are usually normal, though EEGs may later reveal background slowing or generalized discharges. As the disease progresses, MRIs might show signs of brain atrophy or hippocampal damage. While early development often appears typical, delays commonly emerge between 18 and 60 months of age.

In later childhood and adulthood, seizures generally persist, although the frequency of life-threatening prolonged seizures tends to decrease. However, developmental issues such as speech delays, poor coordination, low muscle tone, and walking abnormalities like a crouched gait remain prominent and may worsen over time. Fine motor skills and dexterity are often also affected.

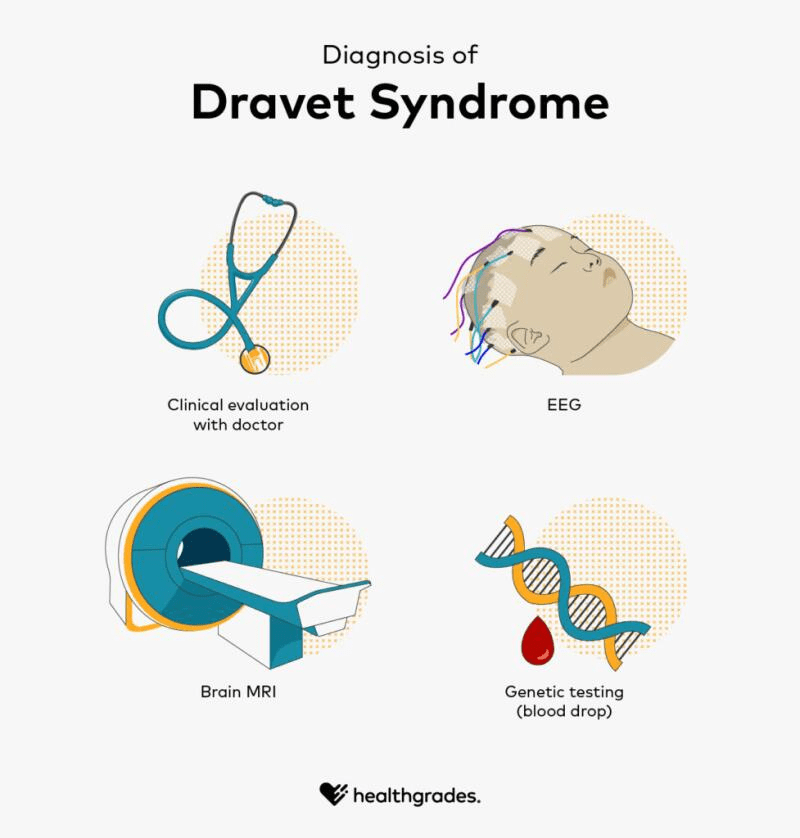

Given the early and severe seizure patterns associated with DS, genetic testing—particularly for SCN1A mutations—is recommended for infants with two or more prolonged generalized or hemiclonic seizures before one year of age, regardless of fever. While an SCN1A mutation supports the diagnosis, it is not definitive on its own, and the absence of such a mutation doesn’t completely rule out DS. Comprehensive evaluation of clinical history and genetic findings is essential for accurate diagnosis.

Causes:

Dravet syndrome is primarily linked to mutations in the SCN1A gene, found in 80–90% of cases. As genetic testing techniques improve—especially in detecting duplications, deletions, and mosaic mutations—this percentage continues to rise. The most common mutation types associated with Dravet include missense (40%), nonsense (20%), frameshift (20%), splice site (10%), and duplications/deletions (7%).

Although milder SCN1A-related disorders are more commonly tied to missense mutations, there’s no consistent relationship between the mutation type or gene location and the severity of Dravet syndrome symptoms. Roughly 90% of SCN1A mutations arise spontaneously and aren’t inherited. In inherited cases, the parent typically has mild epilepsy or is asymptomatic, while the child presents with full Dravet syndrome. Some parents once thought to be mutation-free have later been found to carry mosaic mutations, where only some of their cells carry the genetic change. This happens when a mutation arises early in development, resulting in a mix of mutated and non-mutated cells.

In families with inherited SCN1A mutations, there’s a 50% chance of recurrence in future children. Even for apparently de novo mutations, the risk is still higher than in the general population due to the potential for germ-line mosaicism, so genetic counseling is strongly advised.Other genes, such as SCN2A, SCN8A, GABRA1, GABRG2, PCDH19, STXBP1, and SCN1B, have also been linked to Dravet-like conditions, though these typically show atypical features compared to classic Dravet syndrome.

Diagnosis:

Dravet syndrome is primarily diagnosed based on clinical features rather than genetic testing alone. According to the 2017 consensus of North American specialists, it typically begins between 1 and 18 months of age, most often before a child’s first birthday, with an average onset around 5 months. Early symptoms include recurrent seizures, often generalized tonic-clonic or hemiconvulsive in nature, which can be prolonged but may also be brief. As the child grows, other seizure types emerge—such as myoclonic seizures by age 2, followed by focal seizures, atypical absence seizures, and episodes of obtundation status. Seizures are frequently triggered by fever or overheating from infections, vaccines, baths, or physical exertion, and can also be provoked by visual stimuli, eating, or bowel movements. At the time of onset, development and neurological exams are typically normal, as are brain MRIs and EEGs, which may only show non-specific findings.

As patients age, some symptoms evolve. Seizures tend to persist, though they may become less prolonged and status epilepticus becomes less common in adolescence and adulthood. Sensitivity to heat may also decrease over time. However, seizure control can worsen with sodium channel-targeting medications, which are contraindicated in Dravet syndrome. Cognitive delays often become noticeable between 18 months and 5 years, and many older children and adults develop motor impairments such as hypotonia, incoordination, crouched gait, and reduced fine motor skills. MRI findings in later stages may show mild brain atrophy or hippocampal changes, and EEGs often reveal generalized or multifocal abnormal discharges along with background slowing.

Treatment:

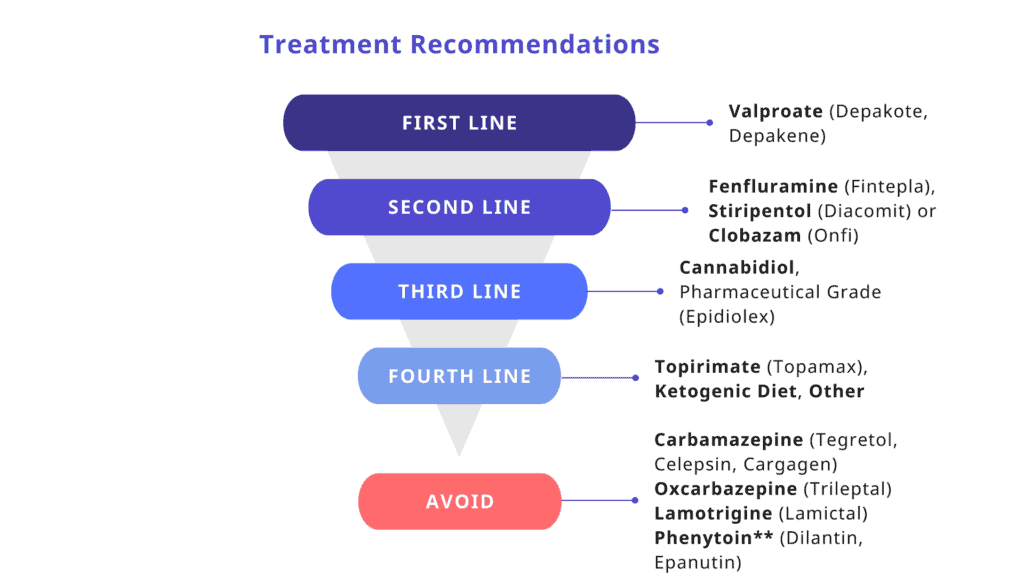

While there is currently no cure for Dravet syndrome, treatment focuses on reducing the frequency and severity of seizures. First-line medications include clobazam and valproic acid, with second-line options such as stiripentol, topiramate, and the ketogenic diet—including its variations like the Modified Atkins Diet—offering additional benefits. Third-line therapies may involve clonazepam, levetiracetam, zonisamide, ethosuximide, and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). Treatment plans are typically personalized, with a combination of medications and dietary strategies used to manage symptoms.

In recent years, new medications have expanded the treatment landscape. Epidiolex (cannabidiol) was FDA-approved in 2018 for patients with Dravet syndrome aged two years and older, marking a significant milestone as the first FDA-approved medication specifically for DS. That same year, stiripentol (Diacomit) was also approved, but only for use in combination with clobazam. In 2020, Fintepla (fenfluramine) received FDA approval as another targeted option for seizure control in DS. Importantly, certain sodium channel blockers—including carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, and others—should be avoided, as they can worsen seizures in this condition. Although phenytoin and fosphenytoin are not recommended for daily use, their effectiveness in emergency settings for status epilepticus remains uncertain. Because prolonged seizures are common in Dravet syndrome, caregivers are often trained to administer rescue medications such as rectal diazepam or intranasal/buccal midazolam to help manage these critical situations at home.

How You Can Make an Impact:

Without proper research, funding, and support for continued studies and clinical trials to determine possible cures, legitimate medicines for the disease, or preventative treatment, many more people will go on to develop Dravet syndrome. If you can, please donate here! If you are unable to donate, consider volunteering your time by raising awareness for this rare disease. If you’re interested in learning more about DS, donation opportunities, or the progress being made on potential treatments, visit the Dravet Syndrome Foundation! The Dravet Syndrome Foundation strives to “aggressively raise funds for Dravet syndrome and related epilepsies; to support and fund research; increase awareness; and to provide support to affected individuals and families.”

Let’s keep spreading awareness! – Lily

References:

Sullivan, Joseph, et al. “Dravet Syndrome – Symptoms, Causes, Treatment | NORD.” NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders), 24 July 2020, rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/dravet-syndrome-spectrum/. Accessed 13 Apr. 2025.

Leave a comment