What is Evans Syndrome?:

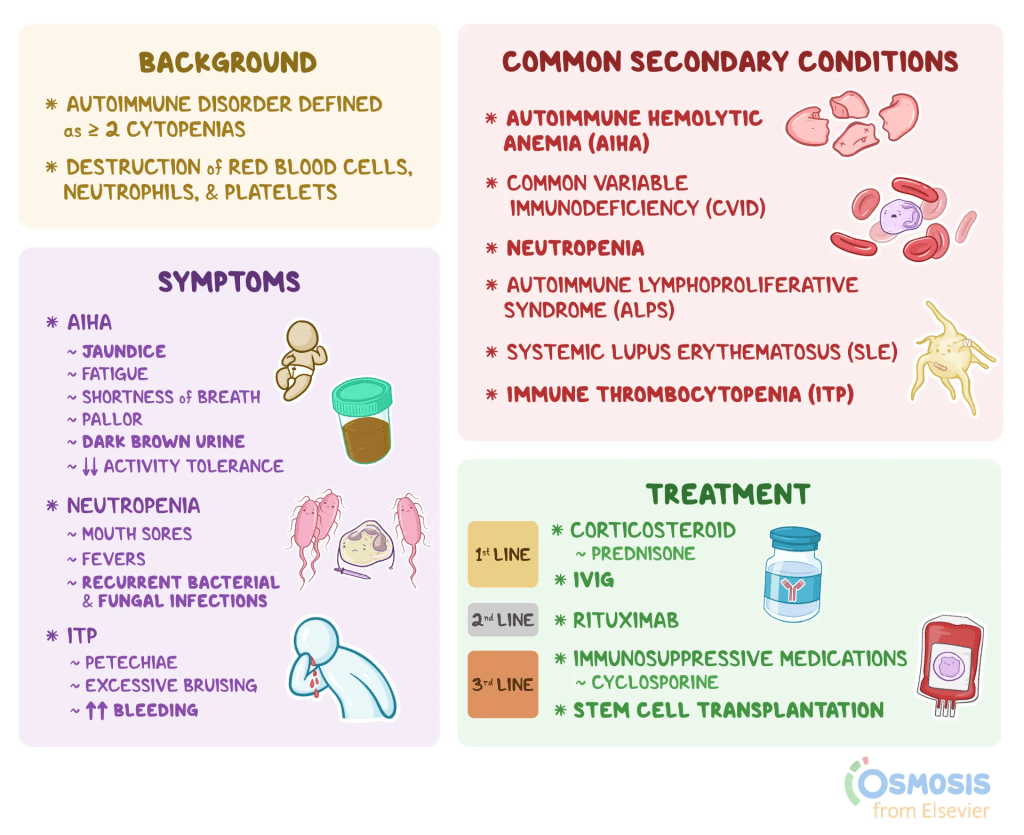

Evans syndrome is a rare autoimmune disorder in which the body’s immune system mistakenly targets and destroys its own blood cells, including red blood cells, platelets, and occasionally neutrophils, a type of white blood cell. This destruction leads to cytopenia, or abnormally low levels of these cells. When red blood cells are affected, it results in autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA); when platelets are low, it is termed idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura (ITP); and a decrease in neutrophils is known as neutropenia. The hallmark of Evans syndrome is the combination of AIHA and ITP, while neutropenia is less common. These conditions can emerge simultaneously or develop one after the other.

The severity and symptoms of Evans syndrome differ significantly among individuals and can sometimes lead to life-threatening complications. The disorder may appear on its own (primary) or in association with other autoimmune or lymphoproliferative diseases (secondary), with the distinction being crucial for determining treatment strategies. First identified by Dr. Robert Evans in 1951, the syndrome was initially seen as a coincidental overlap of immune disorders but is now recognized as a unique condition resulting from chronic immune system dysregulation.

Symptoms:

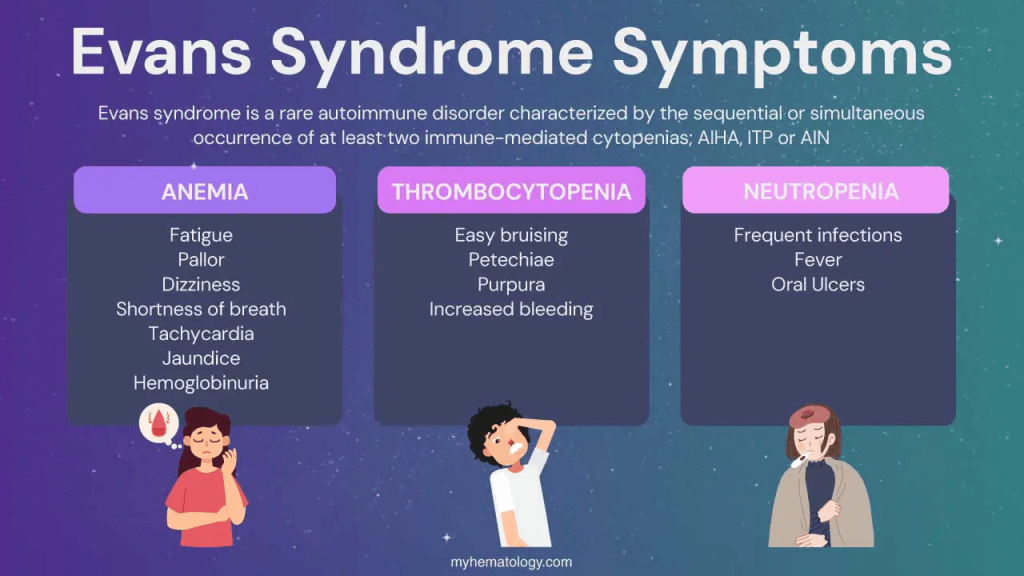

Evans syndrome presents with highly variable symptoms, severity, and progression between individuals. It often follows a chronic pattern marked by flare-ups and temporary improvements after treatment. The symptoms mainly result from low levels of certain blood cells, each with a vital role: red blood cells carry oxygen, platelets help with blood clotting, and white blood cells fight infections.

Some people may first experience rapid destruction of red blood cells, leading to anemia, which can cause fatigue, pale skin, shortness of breath, dark urine, rapid heartbeat, and sometimes jaundice. Others may initially develop thrombocytopenia (low platelets), leading to easy bruising, spontaneous bleeding, and skin changes like petechiae, purpura, and ecchymosis.

Neutropenia (low white blood cells) is less common but can result in recurrent infections, fever, general malaise, and mouth ulcers. Additional symptoms can include swelling of the liver, spleen, or lymph nodes, especially during flare-ups.

In more severe or treatment-resistant cases (refractory Evans syndrome), the condition can lead to life-threatening complications such as severe infections (sepsis), heavy bleeding, and heart problems like heart failure.

Causes:

Evans syndrome is a rare autoimmune condition with an unknown root cause. In this disorder, the immune system mistakenly creates antibodies that attack the body’s own red blood cells, platelets, and sometimes white blood cells. Normally, antibodies defend the body by targeting harmful invaders, but in Evans syndrome they wrongly target healthy cells. These are called autoantibodies.

Researchers think that certain triggers, like infections or other underlying illnesses, may cause the immune system to start producing these harmful autoantibodies. Evans syndrome can also develop as a secondary condition linked to other diseases, such as lupus, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS), antiphospholipid syndrome, Sjogren’s syndrome, common variable immunodeficiency, IgA deficiency, lymphomas, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Diagnosis:

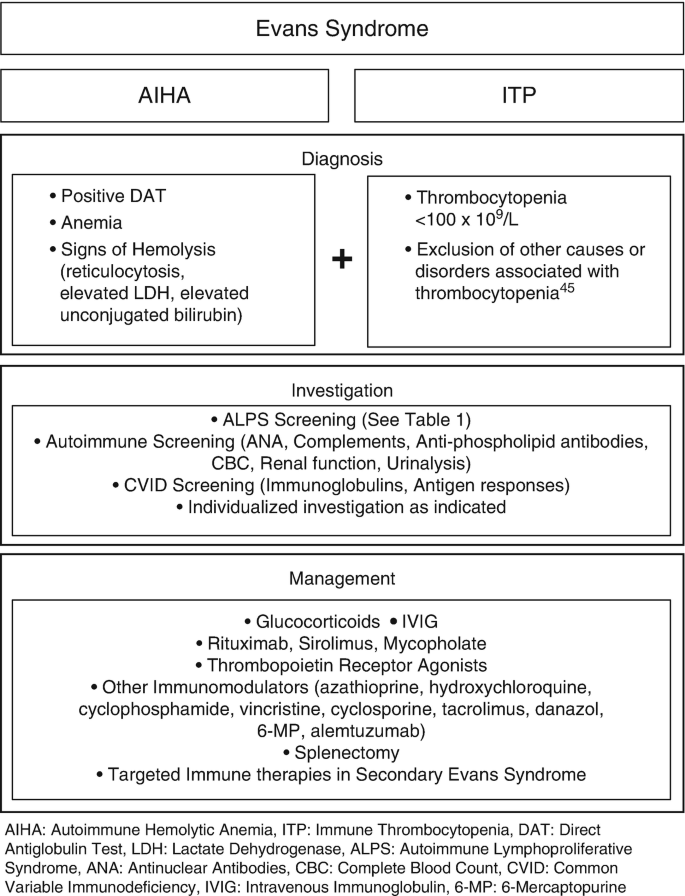

A diagnosis of Evans syndrome is made through a combination of identifying characteristic symptoms, reviewing the patient’s medical history, performing a thorough clinical examination, and conducting specialized tests. There is no single definitive test for Evans syndrome; instead, the diagnosis is reached by excluding other possible conditions. It is typically confirmed when a patient exhibits both autoimmune hemolytic anemia (evidenced by a positive direct Coombs test) and immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), even if the two conditions do not appear at the same time.

To support the diagnosis, various clinical tests are performed. A complete blood count (CBC) can reveal low levels of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. A direct antiglobulin test (DAT) is used to detect abnormal levels of antibodies on red blood cells. Additional tests, such as bone marrow biopsies, antibody screening, and CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, may be used to rule out other potential causes.

In pediatric cases, physicians often recommend screening for autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS), as it commonly co-occurs with Evans syndrome. This involves using flow cytometry to detect elevated levels of double-negative T-cells (DNTs), which are indicative of ALPS.

Treatment:

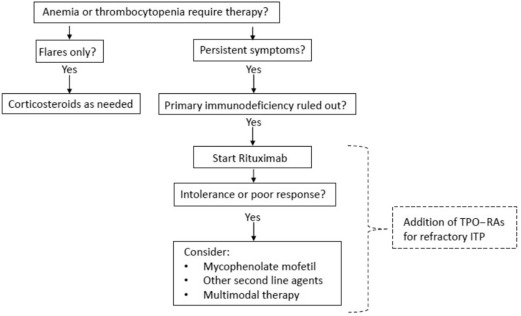

Evans syndrome has no known cure, and treatment can be difficult and highly individualized. Management focuses on addressing each patient’s specific symptoms and typically involves a coordinated approach from a team of specialists, including pediatricians, hematologists, immunologists, and others. While most patients require treatment, a few rare cases may enter spontaneous remission. The effectiveness of treatment varies significantly; some people experience long-term remission, while others deal with persistent or recurring symptoms.

Therapeutic approaches depend on several factors, such as the severity of the condition, blood counts, presence of specific symptoms, age, overall health, and patient preferences. Treatment decisions are made through careful consultation between healthcare providers and the patient, weighing the potential benefits, risks, and long-term impacts.

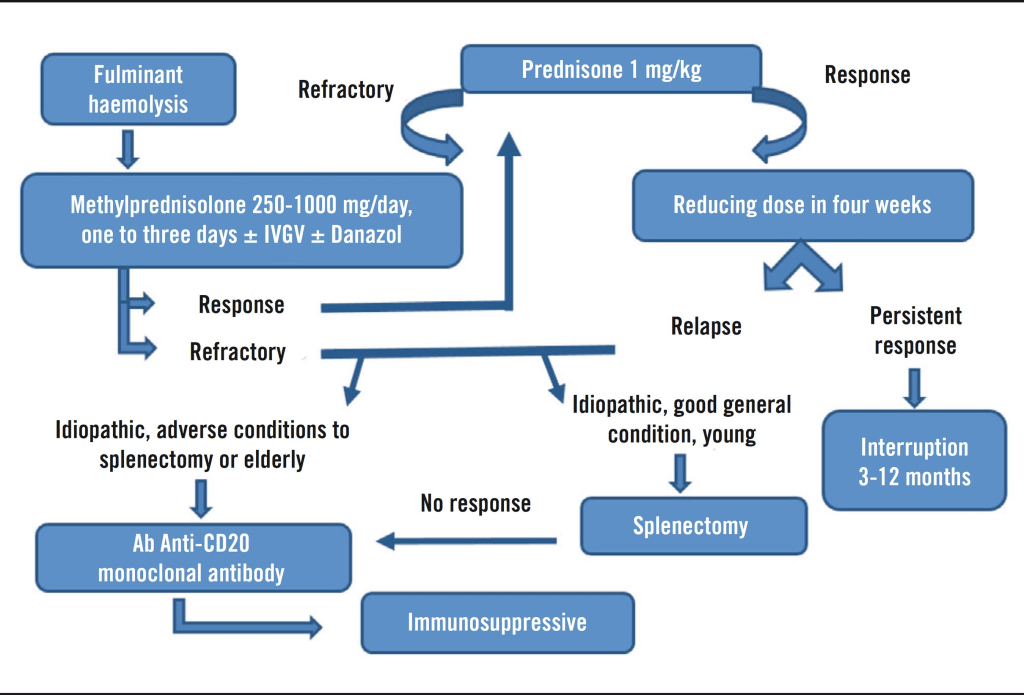

First-line treatment usually involves corticosteroids like prednisolone, which suppress immune activity and reduce autoantibody production. These are often initially effective. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) is another common treatment that helps regulate immune function by introducing healthy antibodies into the bloodstream.

Splenectomy, or surgical removal of the spleen, may be considered in cases that don’t respond to standard treatments. However, its effectiveness is uncertain, especially in children, where long-term remission is rare. In adults, results vary and symptoms often return, so this option is generally delayed as long as possible.

During severe episodes, blood or platelet transfusions may be used to manage symptoms, though they are avoided unless absolutely necessary due to potential complications.

Newer therapies are being explored, with rituximab, a lab-engineered monoclonal antibody, showing promise. It is considered safer than other immunosuppressants but may cause hypogammaglobulinemia, especially in patients with underlying ALPS, making them more vulnerable to infections.

Other medications, such as mycophenolate mofetil, are being tested as second-line or combination treatments for patients who do not respond to steroids or IVIg. Although some early results are encouraging, further research is needed to fully understand the long-term safety and effectiveness of these newer options.

How You Can Make an Impact:

Without proper research, funding, and support for continued studies and clinical trials to determine possible cures, legitimate medicines for the disease, or preventative treatment, many more people will go on to develop Evans Syndrome. If you can, please donate here! If you are unable to donate, consider volunteering your time by raising awareness for this rare disease. If you’re interested in learning more about Evans Syndrome, donation opportunities, or the progress being made on potential treatments, visit the Autoimmune Association. The Autoimmune Association strives “to lead the fight against autoimmune disease by improving healthcare, advancing research, and empowering the community.”

Let’s keep spreading awareness! – Lily

References:

Bussel, J. (2015, July 14). Evans Syndrome – Symptoms, Causes, Treatment | NORD. NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders); NORD. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/evans-syndrome/

Leave a comment