What is EMAtS?:

Epilepsy with myoclonic-atonic seizures (EMAtS) is a rare childhood epilepsy syndrome characterized primarily by seizures that involve sudden muscle jerks followed by a loss of muscle tone. While myoclonic-atonic seizures are the hallmark of the condition, other types of seizures may also occur. EMAtS is classified as a generalized seizure disorder and falls within the GEFS+ (genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus) spectrum. The exact cause is often unknown, though certain gene variants have been linked to the condition. It predominantly affects males at nearly three times the rate of females and typically emerges between 7 months and 6 years of age, often in children who had previously normal development. Diagnosis involves clinical assessment and EEG testing, and treatment may include medications and dietary interventions, with the ketogenic diet proving especially effective. Approximately 60–80% of affected individuals eventually achieve seizure remission, but those with persistent seizures may face challenges such as intractable epilepsy and intellectual disabilities.

Symptoms:

Epilepsy with myoclonic-atonic seizures (EMAtS) is a rare form of epilepsy that typically begins in early childhood, most commonly between the ages of 1 and 5, though about a quarter of cases start before a child’s first birthday. Most children with EMAtS develop normally prior to seizure onset, although around 20% may experience mild developmental delays, particularly in speech.

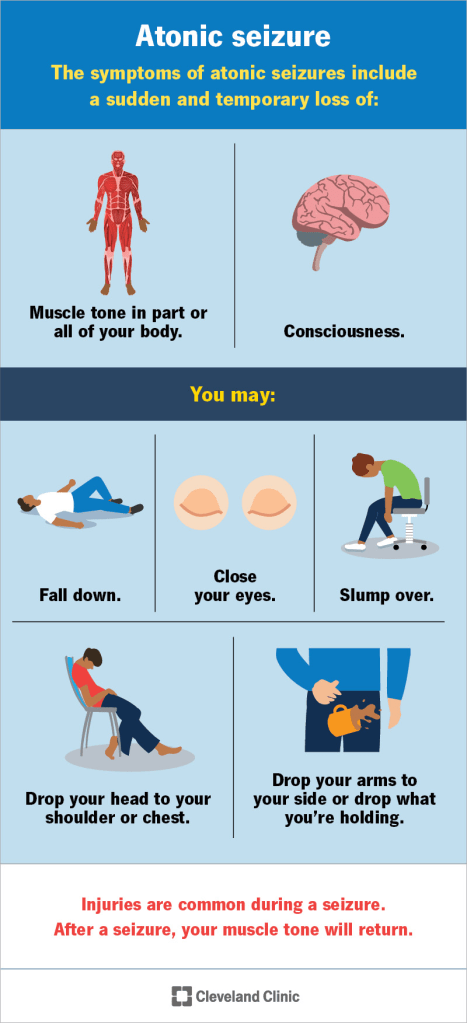

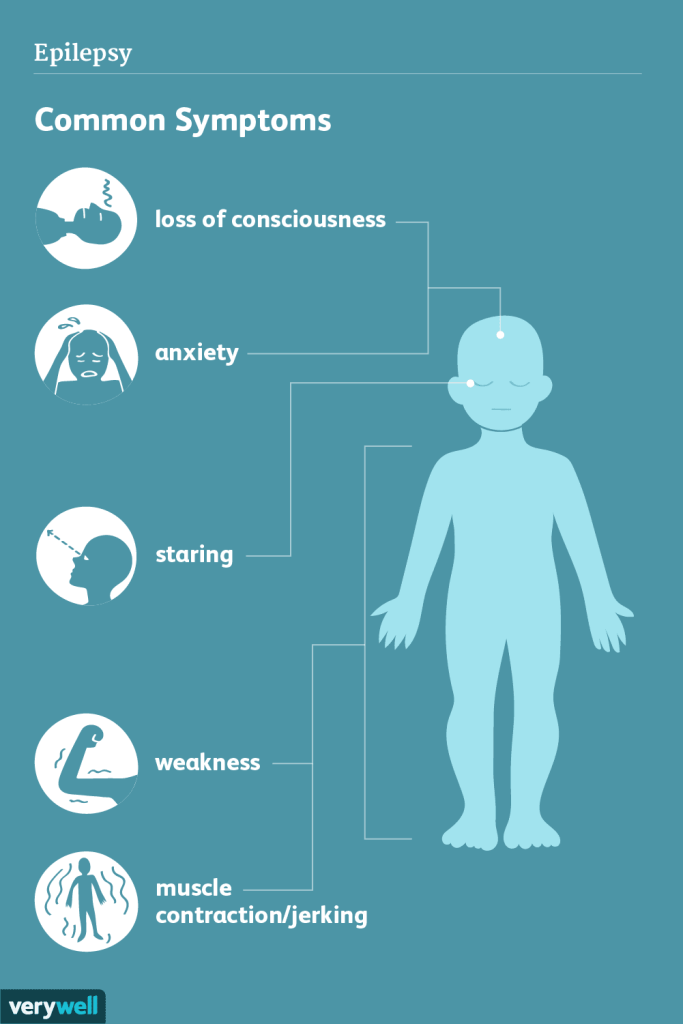

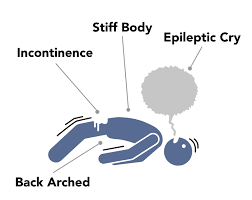

The first seizure is often a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, where the child becomes unconscious and goes through two phases: the tonic phase, marked by muscle stiffening and potential loss of bladder control, and the clonic phase, involving rhythmic jerking movements of the body. As the condition progresses, children often develop multiple seizure types. These may include absence seizures (brief staring spells with minor movements), myoclonic-atonic seizures (sudden jerks followed by muscle collapse, or “drop attacks”), and myoclonic jerks (sudden brief muscle contractions while the child appears awake but unresponsive).

Atypical absence seizures may also occur, characterized by partial unresponsiveness and unusual movements. A serious complication, non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE), can occur more frequently than convulsive status epilepticus in EMAtS. In NCSE, a child may appear dazed or unresponsive for extended periods without visible convulsions, requiring urgent medical treatment. Children with seizures beginning after age 4 are more likely to start with absence seizures.

As EMAtS progresses, seizure frequency can increase dramatically, sometimes reaching 10 to 50 episodes per day. Beyond seizures, many children also experience other challenges, such as ataxia (balance and coordination issues), cognitive impairments ranging from mild to significant, attention disorders like ADHD or ADD in about 15–20% of cases, and mood or behavioral changes, which may be influenced by seizure medications.

Causes:

The exact cause of epilepsy with myoclonic-atonic seizures (EMAtS) remains unknown, though genetic factors appear to play a role in some cases. Around 34–44% of individuals with EMAtS have a family history of epilepsy, though the specific seizure types may differ among relatives. However, these seizure types typically fall within the GEFS+ (genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus) spectrum, a group of recurrent febrile and afebrile seizures seen across multiple generations. Within this spectrum, myoclonic, atonic, and absence seizures are the most common. Genetic variants have been identified in some individuals with EMAtS, with about 14% found to have single-gene (monogenic) mutations. These may be inherited or occur spontaneously (de novo), and are not always present in every affected individual, meaning some people develop EMAtS without any genetic findings or family history.

Several genes have been associated with EMAtS, including SLC6A1, SLC2A1, SCN1A, SCN1B, SCN2A, GABRG2, CHD2, SYNGAP1, NEXMIF, AP2M1, and KIAA2022. Among these, SLC6A1 is frequently linked to more severe forms of the condition and is involved in GABA transmission, which helps regulate nerve activity in the brain. SLC2A1 is associated with GLUT1 deficiency, a disorder that impairs glucose transport to the brain, leading to reduced energy supply and neurological issues, including seizures. In cases involving SLC2A1 or SLC6A1, researchers suggest that the seizures may be part of broader neurological dysfunction rather than caused directly by the gene mutations themselves. Children with genetic variants, especially in these key genes, often experience more severe developmental delays and neurological impairments even before seizures begin.

Diagnosis:

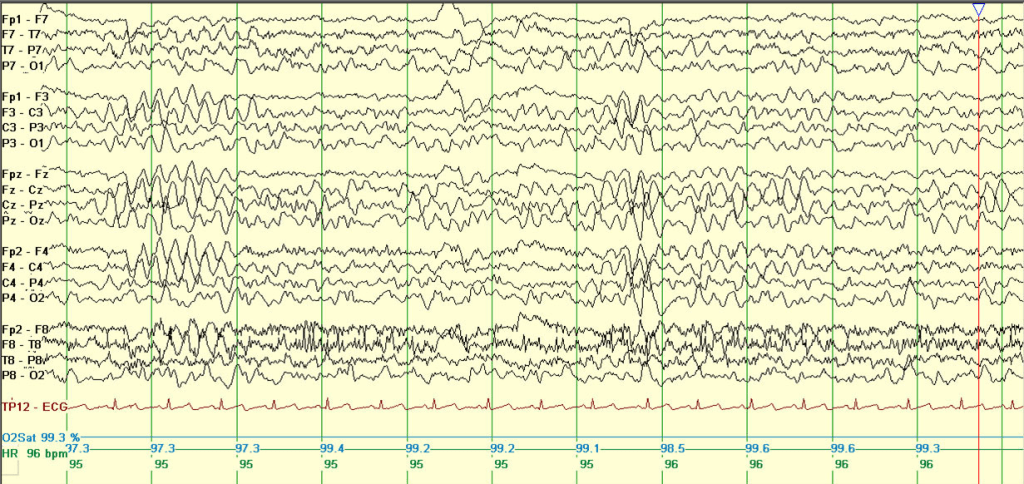

Epilepsy with myoclonic-atonic seizures (EMAtS) is diagnosed based on a combination of clinical presentation and electroencephalogram (EEG) findings. While individuals with EMAtS may experience a variety of seizure types, the presence of myoclonic-atonic seizures is a defining feature of the condition. Most children with EMAtS show typical development before the onset of seizures, though some may have mild developmental delays. The condition usually begins early, with 94% of cases presenting before the age of five. Around 60% of affected children also experience generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Diagnostic imaging such as MRI and blood tests typically appear normal in EMAtS cases. EEGs often reveal characteristic abnormal brain wave patterns, such as “spike and wave” or “polyspike and wave,” although early EEGs may sometimes appear normal. Genetic testing can support the diagnosis, particularly when variants in the SLC2A1 gene are identified. This gene is linked to glucose transport in the brain, and mutations can cause a deficiency in GLUT1 transporters. Since certain SLC2A1 variants respond well to specific treatments, including dietary interventions, genetic sequencing can play a crucial role in guiding management. In some cases, a lumbar puncture may be used to detect low glucose levels in the spinal fluid, further supporting a diagnosis linked to GLUT1 deficiency.

Treatment:

Treatment for epilepsy with myoclonic-atonic seizures (EMAtS) varies significantly from child to child. While about 68% of children eventually outgrow their seizures, others may continue to face challenges and require long-term management. The first line of treatment typically involves anti-seizure medications such as sodium valproate, topiramate, lamotrigine, clobazam, ethosuximide, zonisamide, and levetiracetam. However, only around 25% of children respond well to these medications. Felbamate, a newer drug, has shown promising results in some cases of EMAtS where other medications have failed.

When medications are ineffective, the ketogenic diet is often considered. This high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet shifts the body’s energy source from sugar to fat, which can significantly reduce seizures—by more than 50% in 80–90% of individuals. It is especially effective in children with GLUT1 deficiency and may also support improvements in behavior and cognitive function.

Some anti-seizure drugs can actually worsen seizures in EMAtS. Medications such as vigabatrin, carbamazepine, phenytoin, and sometimes lamotrigine (when myoclonic seizures are predominant) should be used with caution and only under close medical supervision. In certain cases, short-term use of steroids like prednisolone may help reduce seizure frequency, but long-term use carries the risk of serious side effects.

Supportive therapies also play a vital role in management. Occupational therapy can help children develop everyday life skills, physical therapy can improve strength and mobility, and speech therapy can aid in communication development.

The long-term outlook for children with EMAtS varies. Around 60% develop normally, 20% experience mild learning difficulties, and another 20% have moderate to severe developmental delays. Early diagnosis and intervention can improve outcomes, particularly when generalized tonic-clonic seizures are minimized and non-convulsive status epilepticus is prevented.

How You Can Make an Impact:

Without proper research, funding, and support for continued studies and clinical trials to determine possible cures, legitimate medicines for the disease, or preventative treatment, many more people will go on to develop EMAtS. If you can, please donate here! If you are unable to donate, consider volunteering your time by raising awareness for this rare disease. If you’re interested in learning more about EMAtS, donation opportunities, or the progress being made on potential treatments, visit the Epilepsy Foundation. The Epilepsy Foundation strives to “lead the fight to overcome the challenges of living with epilepsy and to accelerate therapies to stop seizures, find cures, and save lives”

Let’s keep spreading awareness! – Lily

My apologies for the delay in this week’s post. I had a severe reaction to a spider bite over the weekend and am just now recovering enough to share.

References:

Alyea, G., & Perczak, B. (2025, May 27). Myoclonic Atonic Epilepsy – Symptoms, Causes, Treatment | NORD. NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/myoclonic-atonic-epilepsy/

Leave a comment