What is Prader-Willi Syndrome?:

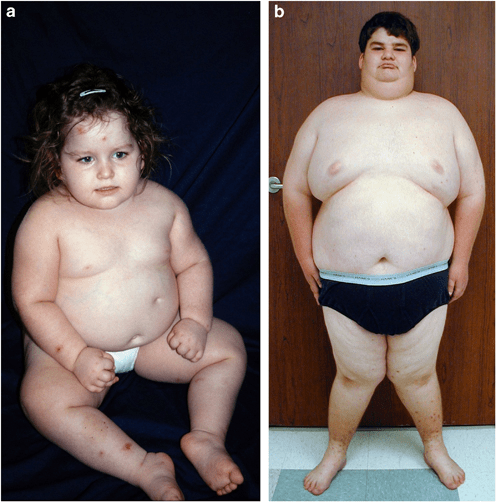

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a complex genetic disorder that affects multiple body systems. In infancy, it is typically marked by symptoms such as low muscle tone (hypotonia), poor sucking ability, feeding difficulties, and inadequate weight gain and growth, often linked to hormone deficiencies. As children grow, they may develop short stature, underdeveloped genitalia, and an insatiable appetite. A hallmark of PWS is the lack of satiety after eating, which can lead to compulsive overeating and, without proper management, severe obesity. This excessive weight gain poses serious health risks, including heart problems, sleep apnea, diabetes, and respiratory issues. Individuals with PWS also commonly experience cognitive challenges, ranging from learning disabilities to mild or moderate intellectual disabilities, along with behavioral issues such as tantrums, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, and skin picking. Developmental delays in motor skills and language are also frequent.

The condition is caused by genetic abnormalities on the long arm of chromosome 15, specifically when genes from the paternal chromosome are missing or inactive. This makes PWS a genomic imprinting disorder, meaning the effect of the genetic change depends on whether it is inherited from the mother or the father. While most cases occur due to random mutations during the formation of egg or sperm cells, some cases may be inherited.

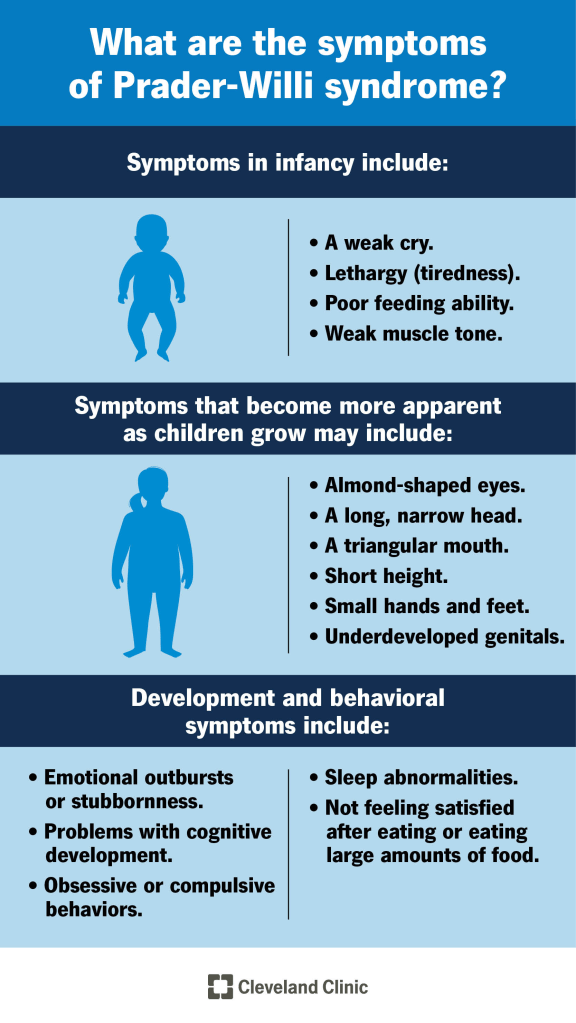

Symptoms:

Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) is a complex genetic disorder that presents a wide range of symptoms, which can vary greatly in type and severity from one individual to another. Many signs of the condition are subtle or develop gradually over time, and not all affected individuals will display every symptom. Because of this variability, it is essential that individuals with PWS are cared for by a medical team familiar with the condition, including genetic specialists who can provide up-to-date information, guide genetic testing, and recommend appropriate treatments.

In infancy, a nearly universal feature of PWS is severe low muscle tone, known as hypotonia. This may be present before birth, leading to decreased fetal movement or abnormal fetal positioning. After birth, infants with PWS are often noticeably “floppy,” have a weak cry, poor reflexes, and significant difficulty feeding due to weak sucking ability. These challenges often result in failure to thrive and may require tube feeding. Hypotonia tends to improve gradually with age, but some degree may persist into adulthood. Affected infants may also have distinctive facial features such as almond-shaped eyes, a thin upper lip, a downturned mouth, a narrow forehead and nose bridge, and an unusually long and narrow head.

As children grow, their feeding ability usually improves and they begin to grow more typically. However, between ages two and four and a half, weight gain often increases without an obvious change in appetite. From about four and a half to eight years of age, appetite tends to increase significantly, often progressing to an overwhelming drive to eat known as hyperphagia. People with PWS do not feel full after eating, which, combined with a reduced need for calories due to low muscle mass, slower metabolism, and limited physical activity, can lead to rapid weight gain and morbid obesity if not closely managed. Not all children with PWS will go through these stages. If left unchecked, obesity can result in serious health complications such as heart and lung disease, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Individuals may resort to eating inedible or unsafe items like spoiled food or garbage and may engage in food hoarding, foraging, or stealing food or money.

Binge eating can also cause dangerous gastrointestinal issues, including severe bloating, stomach rupture, and tissue damage. Many individuals have delayed stomach emptying and difficulties with swallowing. In addition to feeding issues, children with PWS often experience developmental delays. Intellectual ability ranges from borderline or low-normal intelligence with learning disabilities to mild or moderate intellectual disability. Motor and language milestones are frequently delayed.

Despite often having sweet and affectionate personalities, many individuals develop behavioral challenges. These may include temper tantrums, stubbornness, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, manipulative behavior, and skin picking, which can lead to chronic wounds and infections. Some individuals show behaviors similar to those seen in autism spectrum disorders. In adolescence or early adulthood, 10 to 20 percent of affected individuals may develop psychosis. The specific genetic cause of PWS can influence both cognitive and behavioral features.

Hypogonadism, or underfunctioning of the sex glands, is common in PWS. This results in reduced production of sex hormones and can lead to underdeveloped genitals, delayed or incomplete puberty, and infertility. Males may have a small penis, small testes, and an underdeveloped scrotum, often with undescended testes. Females may have a small clitoris or labia, and menstruation may be absent or extremely delayed, sometimes not occurring until adulthood.

Growth hormone deficiency is also a hallmark of PWS, affecting both children and adults. It typically results in short stature and low muscle mass. Early treatment with growth hormone can improve growth, muscle development, and overall body composition. When started in infancy, this therapy can help reduce the health complications associated with PWS and support near-normal growth by adulthood.

Other common physical features include small hands and feet, scoliosis, and hip dysplasia in about 10 percent of individuals. Scoliosis can appear at any age and varies in severity. Sleep problems are frequent and may include excessive daytime sleepiness, abnormal sleep cycles, and sleep apnea. Some individuals with a specific genetic form of PWS may have lighter skin, hair, and eyes compared to their relatives. Vision problems like nearsightedness and misaligned eyes may also occur.

Recurrent respiratory infections are also common, as are other medical issues such as hypothyroidism, low bone density with an increased risk of fractures, temperature regulation difficulties, and swelling or ulcers on the legs, particularly in obese adults. Some individuals may produce thick, sticky saliva and experience a reduced sense of pain or bruise easily. Seizures may also occur in some cases.

Another possible concern is central adrenal insufficiency, a condition in which the body does not produce enough adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) to stimulate cortisol production during times of stress. While its full impact in PWS is still being studied, it may only become apparent during illness or injury. Understanding the natural progression of PWS, including associated medical complications, is important in managing long-term health and planning appropriate care for individuals with this condition.

Causes:

Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) is a genetic disorder that occurs when specific genes on chromosome 15 are either missing or not functioning properly. The affected region, located on the long arm of chromosome 15 at bands q11.2 to q13, is referred to as the Prader-Willi/Angelman syndrome (PWS/AS) region. In individuals with PWS, the issue always arises on the copy of chromosome 15 inherited from the father.

Humans typically have 46 chromosomes in each cell, arranged in 23 pairs, with one chromosome in each pair coming from each parent. These chromosomes contain thousands of genes, which are segments of DNA responsible for various functions and traits. Each chromosome has a short arm (p) and a long arm (q), and each arm is divided into numbered bands to identify gene locations. The PWS/AS region on chromosome 15 is critical for normal development and function.

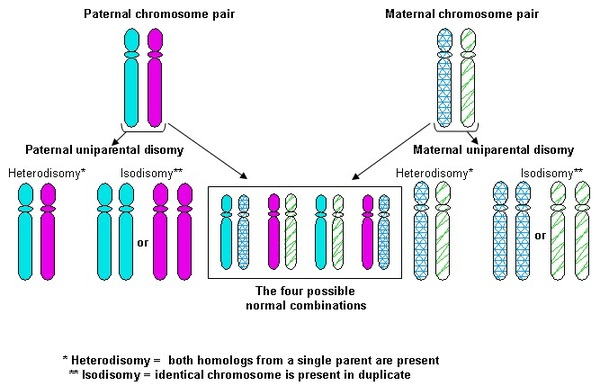

The genetic changes that cause PWS involve either structural abnormalities in the DNA or problems with gene expression, often related to a process called epigenetics. Three main genetic mechanisms are associated with PWS: a deletion in the PWS/AS region of the paternal chromosome 15, maternal uniparental disomy (when both copies of chromosome 15 come from the mother), and imprinting defects that prevent proper gene function.

Genetic imprinting plays a central role in PWS. Normally, individuals inherit one copy of each gene from each parent, and most genes are active regardless of the parent of origin. However, in imprinting, some genes are turned off depending on whether they were inherited from the mother or the father. This process is regulated by chemical changes such as DNA methylation. Errors in imprinting can disrupt normal development and lead to conditions like PWS.

Several imprinted genes are located together in clusters on chromosome 15, regulated by a region known as the imprinting center. In about 60 percent of PWS cases, the father’s PWS/AS region is missing due to a deletion. This deletion usually occurs randomly during development and is not inherited, so the likelihood of it recurring in another pregnancy is very low, typically under 1 percent.

Another 35 percent of cases are due to maternal uniparental disomy, where the individual receives two copies of chromosome 15 from the mother and none from the father. This also results from a random error during development, with a similarly low risk of recurrence.

In less than 5 percent of cases, the paternal chromosome is present but not functioning correctly due to an imprinting defect. These cases may involve mutations or microdeletions in the imprinting center and can be inherited, with up to a 50 percent chance of passing it on to children.

Rarely, PWS results from a chromosomal rearrangement called a balanced translocation, where parts of chromosomes break and reattach in a new configuration. While balanced translocations usually do not affect the person carrying them, they can increase the risk of passing on chromosomal abnormalities to their children, depending on how egg or sperm cells form.

Although several genes have been identified in the PWS/AS region, researchers are still studying their exact functions and how they contribute to PWS symptoms. Many of the disorder’s features are believed to be linked to the dysfunction of the hypothalamus, a brain region that controls hunger, body temperature, mood, sex drive, sleep, and thirst. The hypothalamus also influences hormone release from the pituitary gland, which is responsible for growth and reproductive hormones. This disruption in hormonal regulation is a key factor in the symptoms experienced by individuals with PWS.

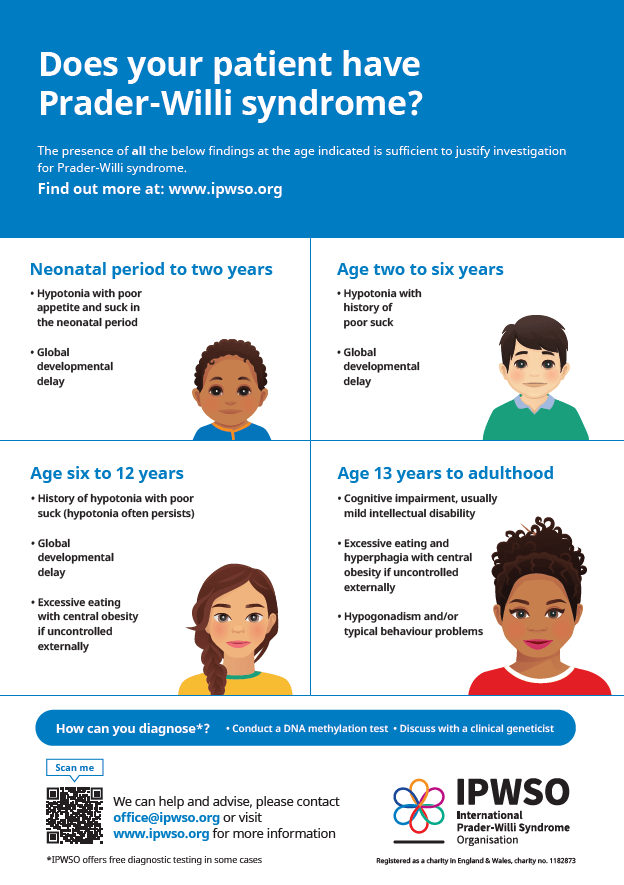

Diagnosis:

The diagnosis of Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) is based on a detailed medical history, a thorough clinical evaluation, and the presence of characteristic signs and symptoms. While standardized diagnostic criteria help identify individuals who may have PWS, genetic testing is essential to confirm the diagnosis and determine the specific genetic cause, such as a deletion in chromosome 15q11-q13, maternal uniparental disomy, or an imprinting defect. Because PWS often presents in newborns with unexplained low muscle tone and poor sucking ability, all such infants should be tested. Confirmation involves specialized genetic tests, including DNA methylation analysis and chromosomal studies like high-resolution microarray testing. These newer technologies can detect small genetic deletions or duplications across the genome, especially in the 15q11-q13 region, which may not be visible through standard chromosome analysis. Microarrays are particularly useful for identifying the common types of deletions in PWS, structural rearrangements, and specific maternal disomy 15 subclasses. These findings are clinically important because the type of genetic change can affect symptom severity, future health risks, and recurrence likelihood within families.

Approximately 99 percent of individuals with PWS can be diagnosed through a DNA methylation test, which determines whether genes in the PWS/AS region of chromosome 15 are active or silenced. A methylation pattern indicating only maternal activity suggests that the paternal gene copy is either missing or not functioning, confirming a diagnosis of PWS. However, while this test confirms the diagnosis, it does not identify the exact cause. Further testing is needed to determine whether the condition is due to a chromosomal deletion, maternal disomy, or an imprinting defect. High-resolution microarrays are now preferred over older techniques like fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) because they can detect both the size and subtype of deletions, as well as identify maternal disomy 15 in individuals without a visible deletion. There are two common deletion subtypes in PWS, referred to as type I (larger) and type II (smaller), and three main forms of maternal disomy 15: heterodisomy, segmental isodisomy, and total isodisomy. Research shows that people with the larger type I deletion tend to have more severe learning and behavioral challenges, while those with maternal disomy 15 may be at increased risk for autistic traits and psychosis during young adulthood. If no deletion is found, further testing can help distinguish between maternal disomy and imprinting center defects.

Prenatal diagnosis is possible, particularly in families with a history of PWS. If a specific genetic abnormality has already been identified in the family, targeted testing can be performed early in pregnancy. Regardless of the underlying cause, prenatal testing using methylation studies or high-resolution microarrays can be done after procedures such as amniocentesis to assess the fetus for PWS.

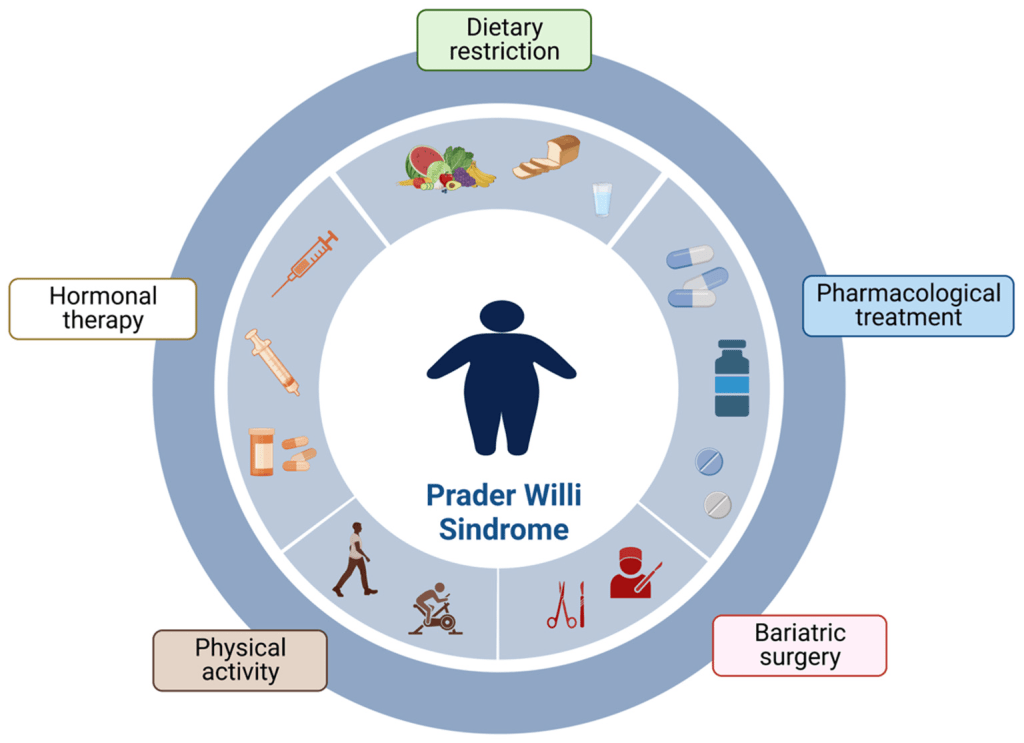

Treatment:

Treatment for Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) focuses on managing the individual symptoms that each person experiences. Early intervention and consistent care can significantly improve both the health and quality of life for individuals with PWS and their families. Treatment usually involves a team of specialists including geneticists, pediatricians, endocrinologists, orthopedists, speech therapists, psychologists, dietitians, and other healthcare professionals. A coordinated care plan is essential to address the complex needs of those with PWS. Genetic counseling is recommended for families after genetic testing has identified the specific subtype of PWS. Parents are strongly encouraged to learn strategies to address the behavioral and eating challenges that are common in PWS, as doing so can lead to better long-term outcomes.

The type of treatment provided depends on factors such as symptom severity, age, overall health, and specific medical findings. Medication and treatment decisions should be made through a personalized medicine approach. This includes analyzing how a patient’s genes affect the way they metabolize certain drugs, helping to guide treatment choices and minimize side effects. Decisions should be made in collaboration with the healthcare team and based on a careful review of the potential risks, benefits, and patient preferences.

Infants with feeding difficulties may need special nipples or a feeding tube to ensure proper nutrition. In some males, early hormone therapy using testosterone or human chorionic gonadotropin may help increase the size of the genitalia or support the descent of the testes if they have not dropped naturally. While hormone treatment may sometimes resolve undescended testes, surgical intervention is often necessary.

One of the most effective treatments for individuals with PWS is growth hormone (GH) therapy. GH can improve height, muscle mass, mobility, and breathing, while reducing body fat. It may also support better development and behavior. In 2000, the FDA approved the use of growth hormone for children with genetically confirmed PWS and signs of growth failure. Studies show that starting treatment as early as two to three months of age provides the greatest benefits. GH therapy has also been shown to improve facial appearance and overall body composition. Standardized growth charts specific to PWS have been developed to monitor growth with or without GH treatment. Before starting GH therapy, it is recommended that a sleep study be performed to check for obstructive sleep apnea. This is important because there have been reports of sudden death in some individuals with PWS who had severe low muscle tone, obesity, or other serious health problems. While the connection to GH therapy is not fully proven, any decisions about treatment should be made in consultation with a pediatric endocrinologist and include screening for adrenal insufficiency.

Early intervention is essential for addressing developmental delays in movement, language, and learning. Physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and special education services should begin as early as possible. An individualized education plan should be developed when the child starts school. Behavioral therapy and, in some cases, medications like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may help manage behavioral challenges or symptoms of psychosis.

Routine medical evaluations are also important. Children should have regular eye exams to identify issues such as strabismus and to check vision. Screening for hip dysplasia and scoliosis should also be part of the medical care plan. Sleep disorders should be evaluated and treated. Regular testing for hypothyroidism and central adrenal insufficiency is recommended because these conditions are more common in individuals with PWS.

To prevent obesity, a structured plan that includes a low-calorie diet, consistent exercise, and strict food supervision should be established early in childhood. This includes monitoring caloric intake based on height, weight, and body mass index. Food access may need to be restricted by locking cabinets and refrigerators. Nutritional supplements, especially calcium and vitamin D, may be necessary for some individuals.

During puberty, hormone replacement therapy can help develop secondary sexual characteristics, improve bone health, and support a positive self-image. However, care must be taken. In males, testosterone injections have been linked to behavioral issues, so transdermal methods like patches or gels are often preferred. In females, hormone therapy carries the same risks as in the general population, such as an increased risk of stroke. Hygiene and other practical concerns should also be considered. Discussions about sex education and contraception are important during adolescence. To help with thick or reduced saliva, special dental care products such as specific toothpastes, gels, rinses, and gum may provide relief.

How You Can Make an Impact:

Without proper research, funding, and support for continued studies and clinical trials to determine possible cures, legitimate medicines for the disease, or preventative treatment, many more people will go on to develop PWS. If you can, please donate here! If you are unable to donate, consider volunteering your time by raising awareness for this rare disease. If you’re interested in learning more about PWS, donation opportunities, or the progress being made on potential treatments, visit the Foundation for Prader-Willi Research. The Foundation for Prader-Willi strives “to eliminate the challenges of Prader-Willi syndrome through the advancement of research and therapeutic development.”

Let’s keep spreading awareness! – Lily

References:

Butler, M. G. (2023, July 12). Prader-Willi Syndrome – Symptoms, Causes, Treatment | NORD. NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders); NORD. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/prader-willi-syndrome/

Leave a comment