What is Hemophilia A?:

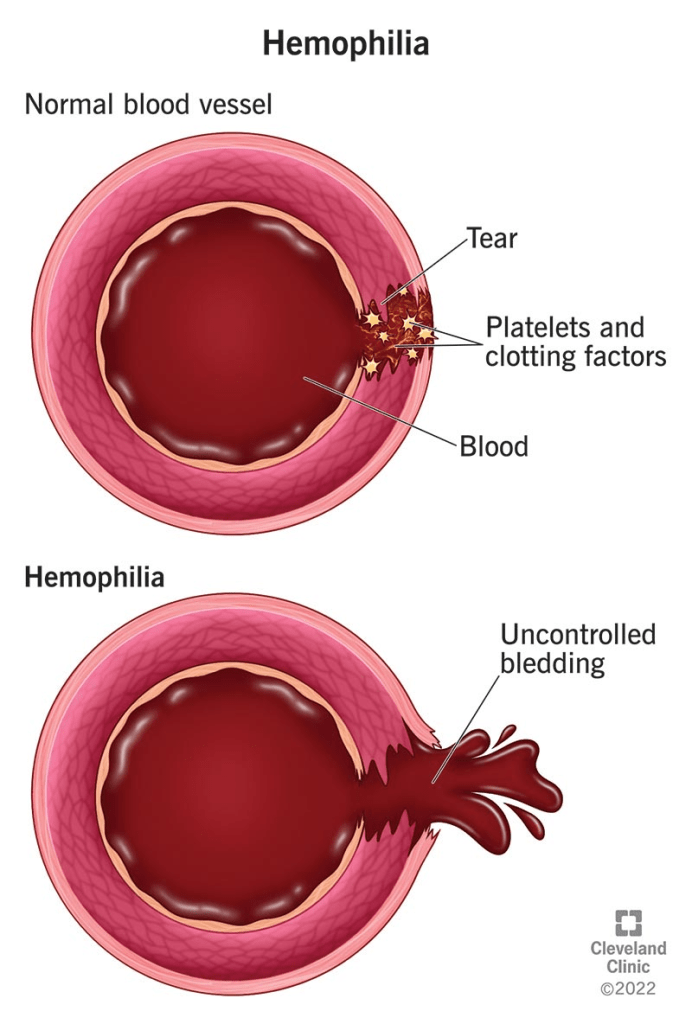

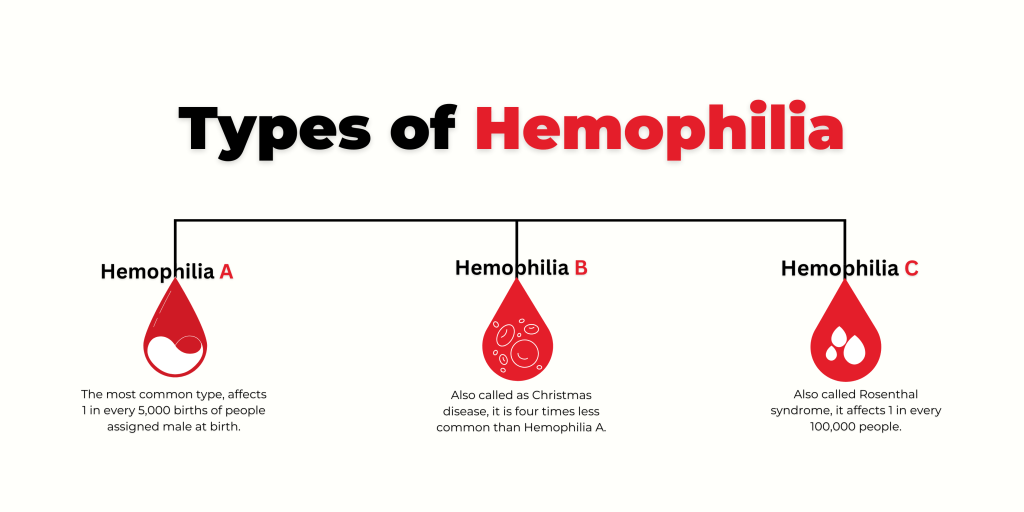

Hemophilia A, also called classical hemophilia, is a genetic disorder that results from low levels of factor VIII, a protein needed for blood clotting. Clotting factors help the blood form clots to stop bleeding. People with hemophilia A do not bleed more heavily than others, but their blood takes longer to clot, leading to extended bleeding after injuries. The severity of the condition depends on how much factor VIII the person produces. Mild cases may only cause problems after surgery, dental work, or injury, while severe cases can lead to long-lasting bleeding from small cuts, large painful bruises, or spontaneous internal bleeding in organs, joints, and muscles.

The disorder is caused by changes in the F8 gene on the X chromosome. These changes can be inherited or appear randomly with no family history. Hemophilia A mainly affects males, though some females who carry the gene may also show symptoms, which are usually mild but can occasionally be severe. While there is no cure, treatments are available that allow most people with hemophilia A to live active and fulfilling lives.

Symptoms:

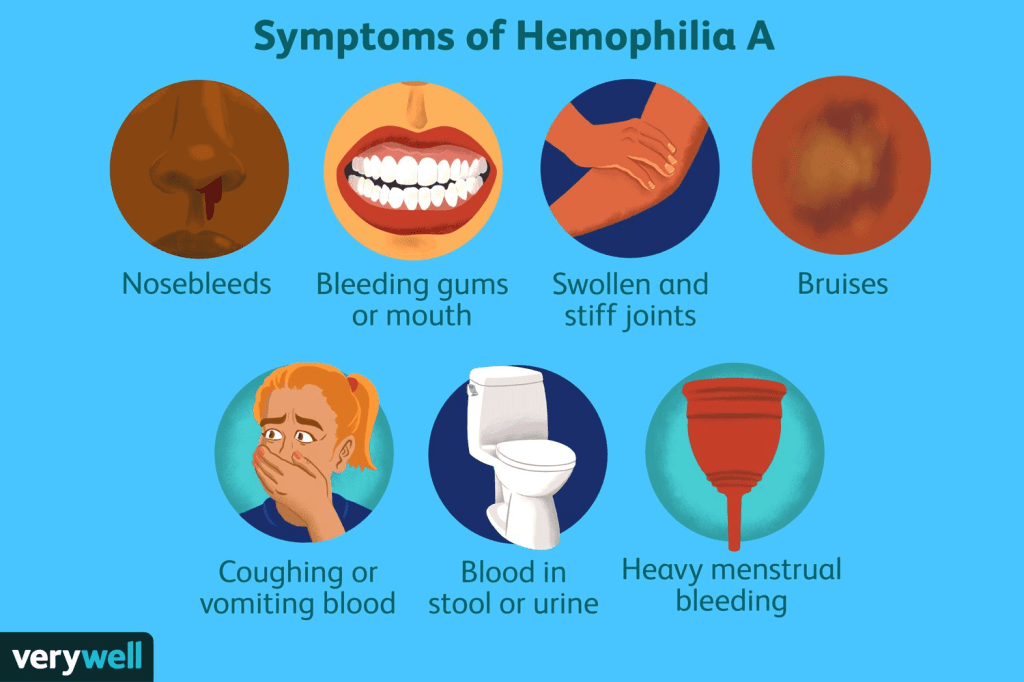

The symptoms and severity of hemophilia A can vary widely. The condition is classified as mild, moderate, or severe, based on the level of factor VIII in the blood. Mild cases have 5 to 40 percent of normal factor VIII activity, moderate cases have 1 to 5 percent, and severe cases have less than 1 percent. The age at which symptoms appear and how often bleeding occurs depend on how much clotting ability the person has. Bleeding episodes are usually more frequent during childhood and adolescence than in adulthood.

Not all people with hemophilia A will show every symptom. It is important for individuals to discuss their specific condition, symptoms, and outlook with their healthcare team.

In mild cases, bleeding may occur from mucous membranes such as the nose or gums, and serious bleeding typically happens only after surgery, dental work, or injury. The bleeding may be more severe than expected for the level of trauma. Some people may not be diagnosed until adulthood, often after a medical procedure or injury causes unexpected bleeding. Many can go years without any major bleeding episodes.

In moderate cases, spontaneous bleeding (without injury) is rare, but prolonged bleeding may occur after surgery, dental procedures, or injury. People may also bruise easily. This form is often diagnosed by early childhood. These individuals have 1 to 5 percent of the normal clotting activity.

Severe hemophilia A involves frequent spontaneous bleeding, usually into the joints or deep muscles, causing pain, swelling, and limited movement. If not treated, repeated joint bleeds can lead to long-term damage and arthritis. Severe cases are usually diagnosed in infancy, often by age two. Infants may bleed after minor mouth injuries or develop large swelling after a bump. Rarely, bleeding can occur in or around the brain at birth. Other signs in untreated infants include firm swellings under the skin called hematomas.

As children with severe hemophilia A grow, they may experience multiple spontaneous bleeds each month if not on preventive treatment. These bleeds can also affect internal organs such as the kidneys, intestines, or brain. Blood may appear in the urine or stool, and bleeding in the brain can cause symptoms like headache, vomiting, seizures, drowsiness, or confusion. Without treatment, these bleeding episodes can become life-threatening.

Causes:

Hemophilia A is caused by changes in the F8 gene, which provides instructions for making factor VIII, a protein necessary for blood clotting. When this gene is altered, the body produces little or no functional factor VIII, leading to the bleeding symptoms seen in hemophilia A.

The F8 gene is located on the X chromosome. About 70 percent of cases are inherited in an X-linked pattern, while the remaining 30 percent arise from new gene changes with no family history.

X-linked genetic conditions primarily affect males, as they have only one X chromosome. If a male inherits an X chromosome with a harmful F8 gene variant from his mother, he will have hemophilia A. Females have two X chromosomes, so if only one carries the faulty gene, they are typically carriers and usually do not have symptoms because the other X chromosome provides a working copy of the gene.

Carrier females have a 25 percent chance in each pregnancy of passing the gene variant to a son, who would then have hemophilia. They also have a 25 percent chance of having a daughter who is also a carrier. Sons who do not inherit the faulty gene will be unaffected, and daughters who inherit two healthy copies will not be carriers.

If a male with hemophilia has children, he will pass the gene variant to all of his daughters, making them carriers, but none of his sons will inherit the condition because they receive his Y chromosome instead of his X.

In females, one of the X chromosomes is usually inactivated in each cell. If the X chromosome carrying the healthy F8 gene is mostly inactivated, a female carrier may show symptoms of hemophilia. In such cases, she may appear to have mild hemophilia. Rarely, other genetic factors can cause a female to develop hemophilia A even without being a typical carrier.

Diagnosis:

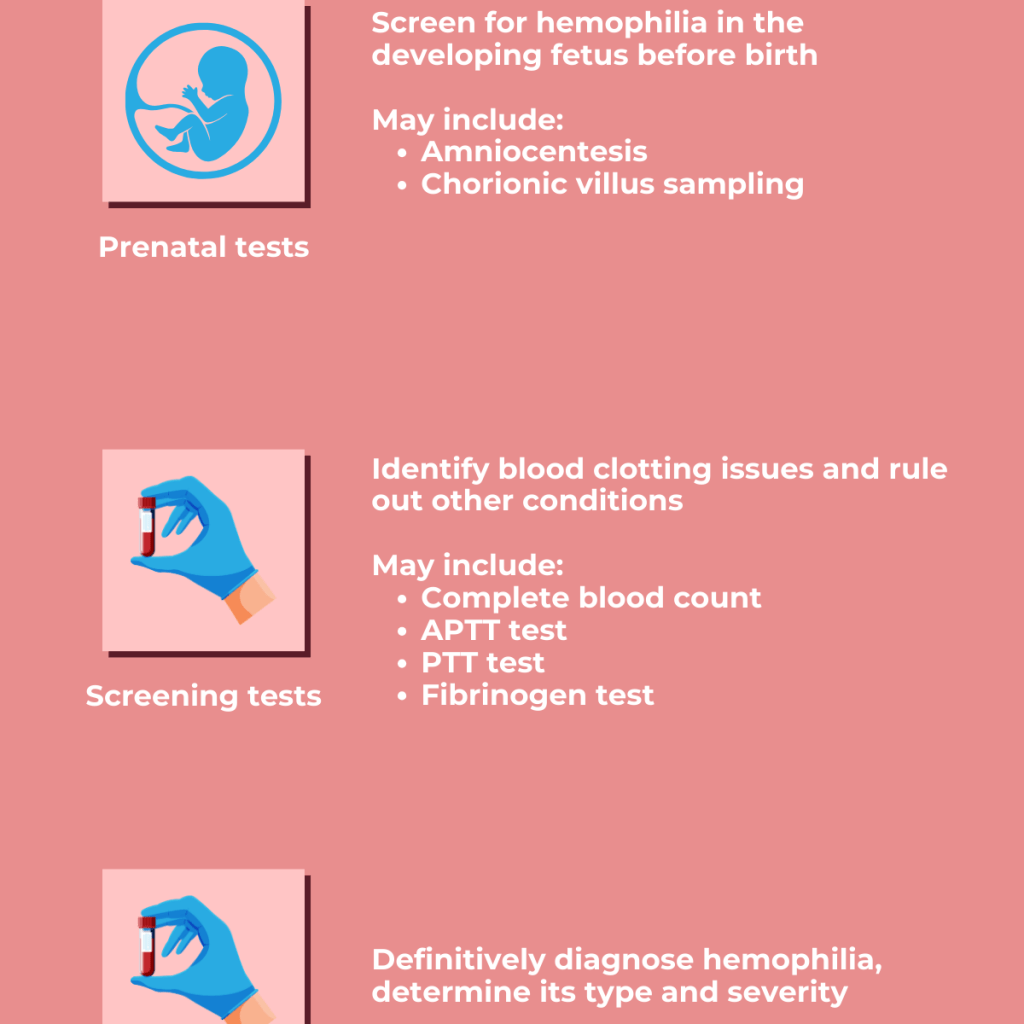

Diagnosing hemophilia A involves recognizing key symptoms, reviewing the patient’s medical history, performing a clinical exam, and conducting specific lab tests.

Doctors typically order a complete blood count (CBC), clotting tests, and measurements of clotting factor levels, especially factor VIII. Two common screening tests are activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT). In hemophilia A, the PT result is usually normal, while the aPTT is often prolonged if factor VIII levels are below 30 percent of normal. If aPTT is abnormal, a clotting activity assay is used to confirm the diagnosis. This test identifies whether the deficiency is in factor VIII, which confirms hemophilia A, or in another clotting factor. It also helps determine how severe the deficiency is. However, mild cases may not always show up on an aPTT test, so a normal result does not rule out the condition.

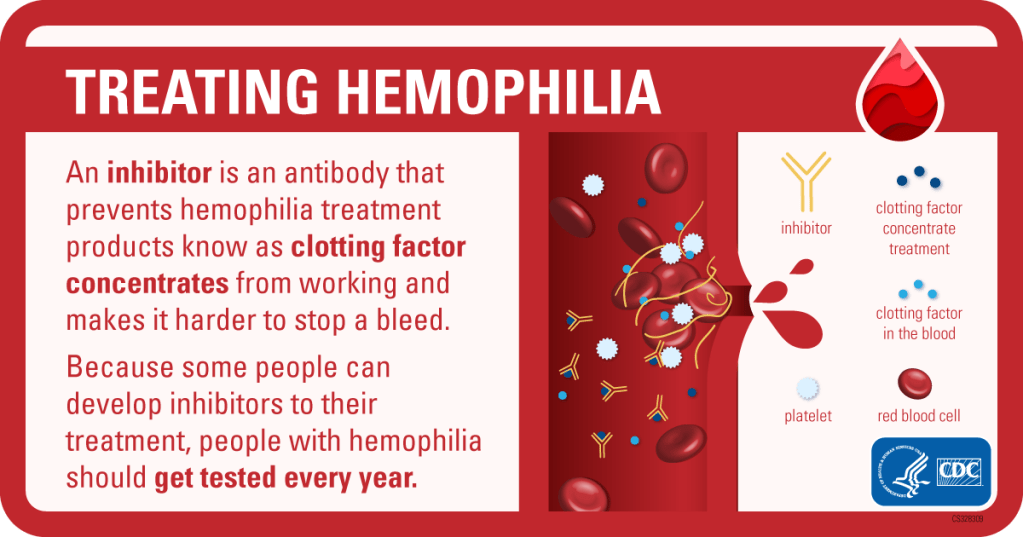

After confirming hemophilia A, genetic testing is usually done to identify the specific change in the F8 gene. This information can help predict whether the person might develop a complication called an “inhibitor.” Inhibitors are antibodies that block the effect of replacement therapy, making treatment less effective. In some cases, allergic reactions may also occur.

Genetic testing can also identify female carriers in a family and is useful for prenatal diagnosis. With current technology, such as digital PCR, doctors can detect hemophilia A non-invasively by analyzing fetal DNA in the mother’s blood as early as 7 weeks into pregnancy.

Treatment:

Individuals with hemophilia A benefit from care at federally funded hemophilia treatment centers. These centers offer specialized and comprehensive care, including personalized treatment plans, regular monitoring, and access to a professional healthcare team. This team typically includes physicians, nurses, physical therapists, social workers, and genetic counselors who are experienced in managing bleeding disorders. Genetic counseling is strongly recommended for individuals and their families to better understand inheritance patterns, risks, and treatment options.

Although there is no cure for hemophilia A, current treatments are highly effective. The standard treatment involves replacing the missing clotting protein, factor VIII. This can be done using recombinant factor VIII produced in a lab or plasma-derived factor VIII from blood donations. Recombinant products are often preferred because they carry no risk of transmitting bloodborne infections. Examples of FDA-approved recombinant products include Advate, Helixate FS, Recombinate, and Eloctate. Plasma-derived products such as Koate-DVI and Hemofil M are also available and considered safe due to modern screening and virus-inactivation methods.

Individuals with mild or moderate hemophilia A are usually treated with factor replacement only during bleeding episodes, a method known as “on-demand” therapy. In contrast, those with severe hemophilia A often receive preventive treatment, which involves regular infusions of factor VIII to avoid bleeding episodes and long-term joint damage. Training for home infusions is commonly provided, allowing individuals or parents to administer treatment quickly, which is most effective when given within the first hour of bleeding.

Additional treatment options for mild hemophilia A include desmopressin, a synthetic hormone that temporarily increases factor VIII levels. This can be administered by injection or nasal spray. Antifibrinolytic medications may also be used to help stabilize blood clots, especially during dental procedures or minor bleeding.

Some individuals, particularly those with severe hemophilia A, may develop inhibitors. These are antibodies that the immune system produces in response to the replacement factor VIII, recognizing it as a foreign substance and blocking its effectiveness. Inhibitors occur in approximately 30 percent of individuals with severe disease. The likelihood of developing inhibitors is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors and can vary over a person’s lifetime. Inhibitors are measured in Bethesda units, and the severity can be classified as low- or high-responding depending on how strongly the immune system reacts to repeated exposure.

When inhibitors are present at low levels, bleeding can sometimes be managed with higher doses of factor VIII. However, in cases where the inhibitor level is high, alternative treatments known as bypassing agents are used. These include recombinant activated factor VII (NovoSeven RT) and activated prothrombin complex concentrate (FEIBA). These agents help promote clotting without the need for factor VIII. Although effective, these treatments do not work for everyone and must be carefully managed.

Another approach for individuals with inhibitors is immune tolerance induction (ITI). This involves giving frequent high doses of factor VIII over a long period to retrain the immune system not to react against it. ITI can take months or even years and is successful in about 70 percent of patients. Despite its effectiveness, ITI is costly, time-consuming, and inconvenient for many families.

Gene therapy has recently emerged as a major advancement in treatment. In 2023, the FDA approved Roctavian, a one-time gene therapy designed for adults with severe hemophilia A who do not have pre-existing immunity to the therapy’s viral vector. Roctavian delivers a healthy copy of the F8 gene to the liver, enabling the body to produce its own factor VIII and reducing the need for regular infusions.

In addition to gene therapy, newer non-factor-based treatments are changing the management of hemophilia A. Emicizumab is a lab-engineered antibody that mimics the role of factor VIII and can be injected subcutaneously. It significantly reduces bleeding in people with or without inhibitors and has become a widely used alternative to regular infusions. Another treatment, marstacimab, approved in 2024, targets a protein called TFPI to enhance clot formation and is taken once weekly. It is approved for individuals 12 years and older who do not have inhibitors.

Fitusiran, approved by the FDA in 2025, is a small RNA-based therapy that lowers levels of antithrombin, promoting blood clotting even in individuals with inhibitors. It requires only a few subcutaneous injections per year, offering a lower treatment burden and strong protection against bleeding episodes.

Overall, while hemophilia A remains a lifelong condition, advancements in treatment, including factor replacement, immune tolerance therapy, gene therapy, and newer medications have greatly improved outcomes and quality of life for most individuals. With appropriate care and monitoring, people with hemophilia A can lead healthy, active lives.

How You Can Make an Impact:

Without proper research, funding, and support for continued studies and clinical trials to determine possible cures, legitimate medicines for the disease, or preventative treatment, many more people will go on to develop Hemophilia A. If you can, please donate here! If you are unable to donate, consider volunteering your time by raising awareness for this rare disease. If you’re interested in learning more about Hemophilia A, donation opportunities, or the progress being made on potential treatments, visit the National Bleeding Disorders Foundation. The National Bleeding Disorders Foundation strives to “[find] cures for inheritable blood and bleeding disorders and to addressing and preventing the complications of these disorders through research, education, and advocacy enabling people and families to thrive.”

Let’s keep spreading awareness! – Lily

References:

Almeida-Porada, G. D., Key, N., & Roberts, H. R. (2015, May 19). Hemophilia A – Symptoms, Causes, Treatment. NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders); NORD. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/hemophilia-a/

Leave a comment