What is ALS?:

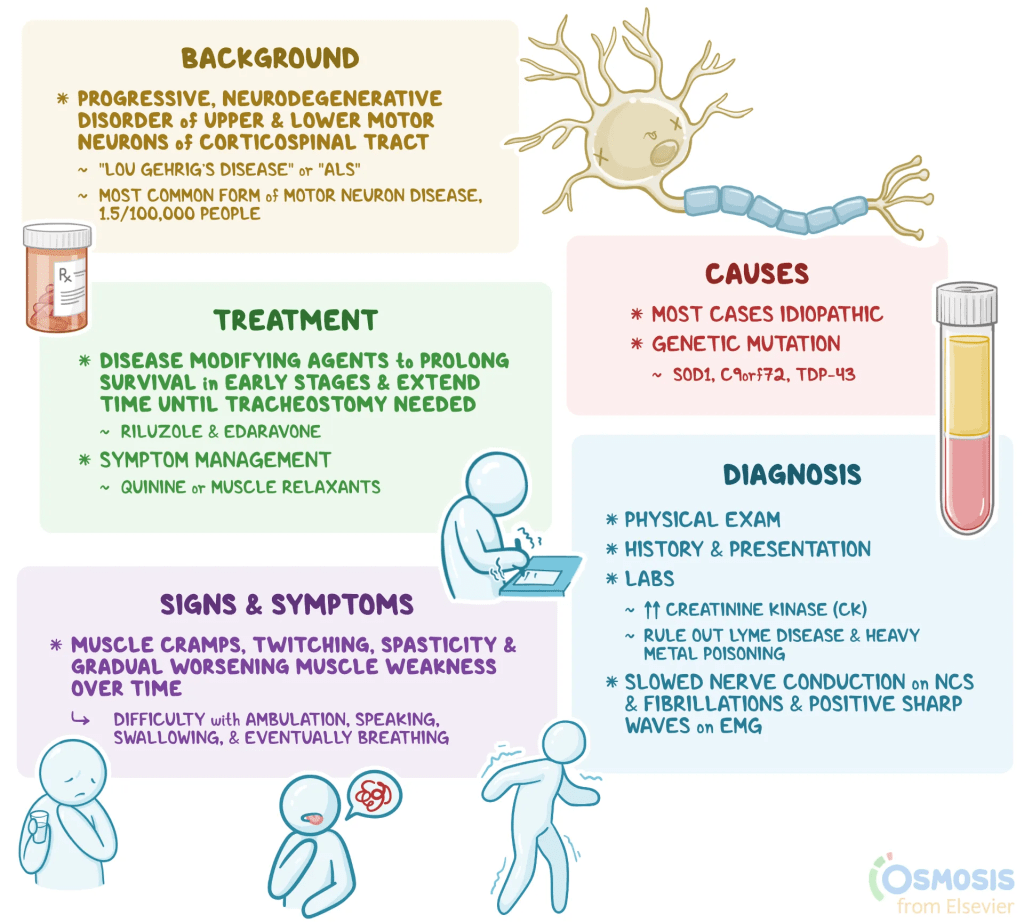

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a disease that causes nerve cells in the brain, brainstem, and spinal cord to slowly stop working and die. These nerve cells, called motor neurons, help the brain send signals to the muscles that control movement. Normally, motor neurons in the brain send messages to those in the spinal cord and brainstem, which then pass the signals to the muscles. In ALS, both sets of motor neurons are damaged, so messages from the brain cannot reach the muscles. Over time, the muscles become weaker and smaller, making it hard to move, speak, swallow, hold up the head, or breathe. The disease continues to worsen and eventually causes breathing failure because the chest and diaphragm muscles no longer work. Treatments that can slow ALS have only limited effects, so care mainly focuses on managing symptoms and providing supportive, team-based care.

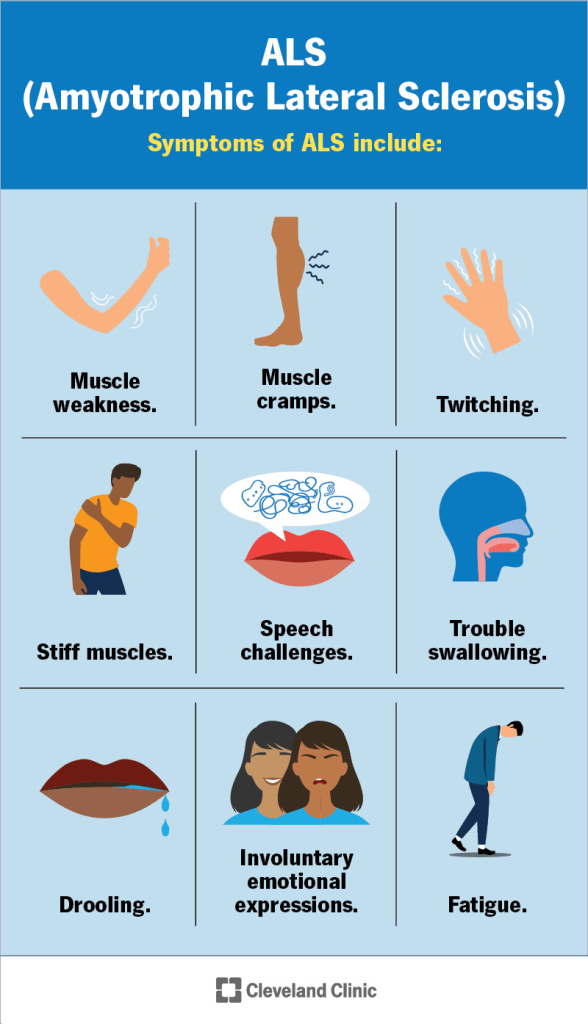

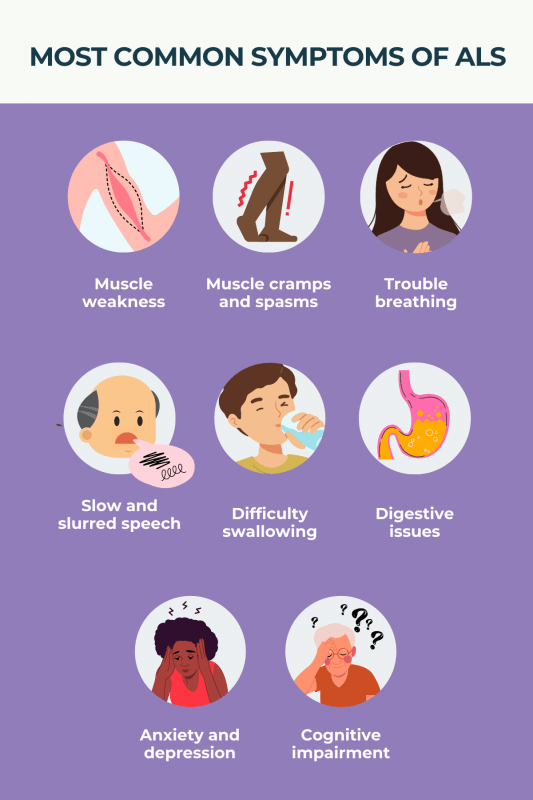

Symptoms:

ALS affects both upper and lower motor neurons, and the symptoms depend on which muscles are involved and which type of motor neuron is more affected. Problems with upper motor neurons cause muscle weakness, stiffness, tightness, stronger reflexes, and difficulty with speech and swallowing. Problems with lower motor neurons cause muscle weakness, shrinking of muscles, lower muscle tone, weaker reflexes, muscle twitching, cramps, and trouble speaking, swallowing, or breathing.

When ALS affects the arms, legs, or body muscles, people may have trouble walking, fall more often, or find daily activities harder to do. When it affects the nerves that control the head and neck, it can cause bulbar symptoms such as difficulty swallowing, speaking, and weakness in the face or tongue. Trouble swallowing can lead to choking, drooling, weight loss, and pneumonia if food or liquids enter the lungs. Bulbar symptoms can also cause sudden and uncontrollable laughing or crying.

ALS symptoms can start at any time in adulthood but usually appear between ages 55 and 75. Rare genetic types can begin in childhood. Early symptoms may include weakness or clumsiness in the hands or legs, difficulty with fine movements, tripping, or falling. Most people first notice symptoms in the arms or legs (spinal-onset ALS), while about one-third begin with problems in speech or swallowing (bulbar-onset ALS). Less often, the first sign is shortness of breath due to weak breathing muscles.

As ALS worsens, more muscles become affected, and weakness increases over time. The disease usually progresses over three to five years, leading to loss of walking and standing ability. Many people eventually need help to breathe. A small number experience slower progression and may remain stable for a while.

Although ALS mainly affects motor function, up to half of patients also have changes in thinking or behavior. About one in ten develop a related condition called behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, which can cause problems with judgment, impulse control, and behavior. Others may have mild thinking or mood changes, including depression or emotional instability. Because movement becomes limited, patients are also at higher risk of developing blood clots.

Causes:

The exact cause of ALS in people without a known gene change, often called sporadic ALS, is not yet understood. Researchers believe that several cell processes go wrong and work together to cause the disease. These include problems with how proteins are made, folded, and moved inside cells, overstimulation of nerve cells, oxidative stress, inflammation in the nervous system, and malfunctioning of mitochondria, which provide energy for cells. These problems lead to the injury and death of motor neurons, resulting in the symptoms of ALS. The only known risk factors are older age and having a family history of the disease.

About ten percent of ALS cases are inherited and are caused by changes in certain genes. More than twenty-five genes have been linked to ALS. Most inherited cases follow a dominant pattern, meaning that one changed copy of a gene is enough to cause the disease, though other inheritance patterns can occur. Some people who carry a disease-causing gene may never develop ALS. The age when symptoms begin and how the disease progresses can vary, even among people with the same gene change.

In people of European background, the most common genetic cause of inherited ALS is a change in the C9ORF72 gene, which can also cause frontotemporal dementia or both conditions together. The second most common cause involves changes in the SOD1 gene. Together, changes in C9ORF72 and SOD1 account for about half of inherited ALS cases. Another fifth are linked to changes in the TARDBP and FUS genes. These gene changes are all linked to dominant forms of the disease.

In dominant genetic conditions, one altered copy of a gene can cause illness. The altered gene can be passed from either parent or can appear for the first time in the affected person. Each child of a parent with the altered gene has a fifty percent chance of inheriting it, and this risk is the same for both males and females.

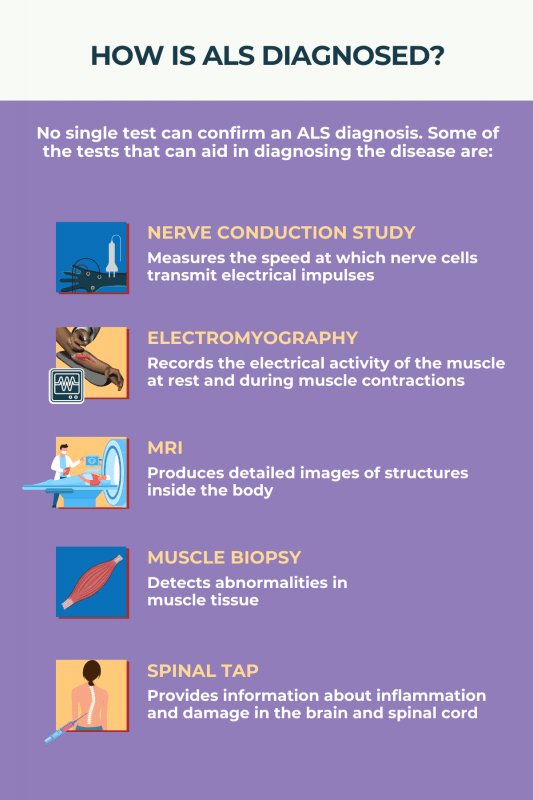

Diagnosis:

ALS is diagnosed based on a doctor’s evaluation rather than a single test. This means that the diagnosis depends on a detailed medical history and a thorough neurological examination. Tests such as blood work or imaging may be used to rule out other possible conditions.

To diagnose ALS, doctors look for a pattern of muscle weakness that gradually spreads to other parts of the body, along with signs that both upper and lower motor neurons are affected. In the early stages, only one type of motor neuron problem may be noticeable.

Tests that measure how well nerves and muscles work, such as electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (NCS), can help confirm that the motor neurons are not functioning properly. Brain scans such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are also done to make sure the symptoms are not caused by another disease.

Genetic testing is especially useful when there is a family history of ALS and is recommended for everyone diagnosed with the condition. Because the symptoms can resemble other diseases, it often takes time to confirm ALS, with the average delay between the first symptoms and diagnosis being about one year.

Treatment:

Treatment for ALS involves a team of healthcare professionals working together to address all aspects of the disease. This team usually includes neurologists, physical and speech therapists, lung specialists, social workers, nutritionists, psychologists, and nurses trained in ALS care. Working with a multidisciplinary team has been shown to help people live longer and improve their quality of life.

ALS treatment focuses on two main areas: therapies that can slow the disease and treatments that manage symptoms and help maintain comfort and function. There is currently no cure for ALS.

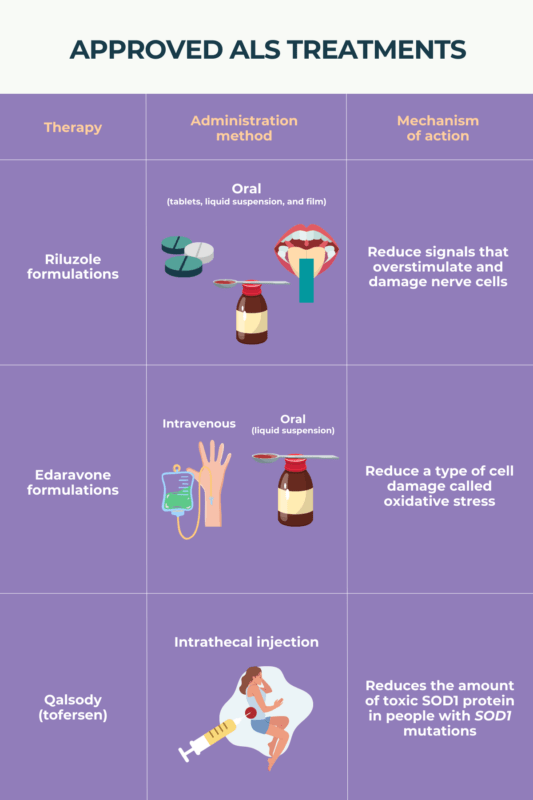

Disease-modifying therapy includes medications that may slightly slow the progression of the disease. Riluzole was the first drug approved for ALS and can extend survival by a few months, though it does not stop muscle weakening. Edaravone has shown some benefit in slowing decline in early ALS, although later studies have produced mixed results. In 2023, the drug tofersen was approved to treat people who have a specific genetic form of ALS caused by a change in the SOD1 gene. It can help slow loss of function and may stabilize symptoms with continued use.

Symptomatic therapy aims to relieve symptoms and improve daily life. This includes both medication and non-medication treatments. Muscle stiffness and twitching can be treated with drugs such as baclofen, tizanidine, or diazepam. In severe cases, baclofen may be given through a small pump placed under the skin. Some people may also benefit from cannabinoids. Painful muscle cramps can be treated with medications like quinine sulfate, levetiracetam, or mexiletine. Excess saliva can be reduced with medicines such as atropine, scopolamine, or amitriptyline, or by using oral suction devices. Emotional or behavioral symptoms, such as depression or changes linked to frontotemporal dementia, can be treated with antidepressants. Pain management is tailored to the individual’s needs.

Physical and occupational therapy are key parts of ALS care. Daily stretching and movement exercises help keep joints flexible and prevent muscles from becoming fixed or tight. Maintaining proper nutrition is also very important, since weight loss is linked to worse outcomes. People who have trouble swallowing should choose soft foods or, if needed, use a feeding tube to ensure enough calories and fluids. Speech therapy and communication devices can help those with speech difficulties.

As breathing muscles weaken, non-invasive ventilation can help patients breathe more easily. Devices that assist with coughing can help clear mucus from the lungs. When breathing becomes too difficult, some patients choose to have a tracheostomy and permanent ventilation, while others may prefer comfort-focused care through hospice services at home. Each treatment plan is personalized to support the person’s choices and quality of life as the disease progresses.

How You Can Make an Impact:

Without proper research, funding, and support for continued studies and clinical trials to determine possible cures, legitimate medicines for the disease, or preventative treatment, many more people will go on to develop ALS. If you can, please donate here! If you are unable to donate, consider volunteering your time by raising awareness for this rare disease. If you’re interested in learning more about ALS, donation opportunities, or the progress being made on potential treatments, visit the ALS Association. The ALS Association is “dedicated to finding a cure for ALS.”

Let’s keep spreading awareness! – Lily

References:

Leveille, E. (2025, March 28). Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis – Symptoms, Causes, Treatment | NORD. NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders); NORD. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/amyotrophic-lateral-sclerosis/

Leave a comment