What is Progeria?:

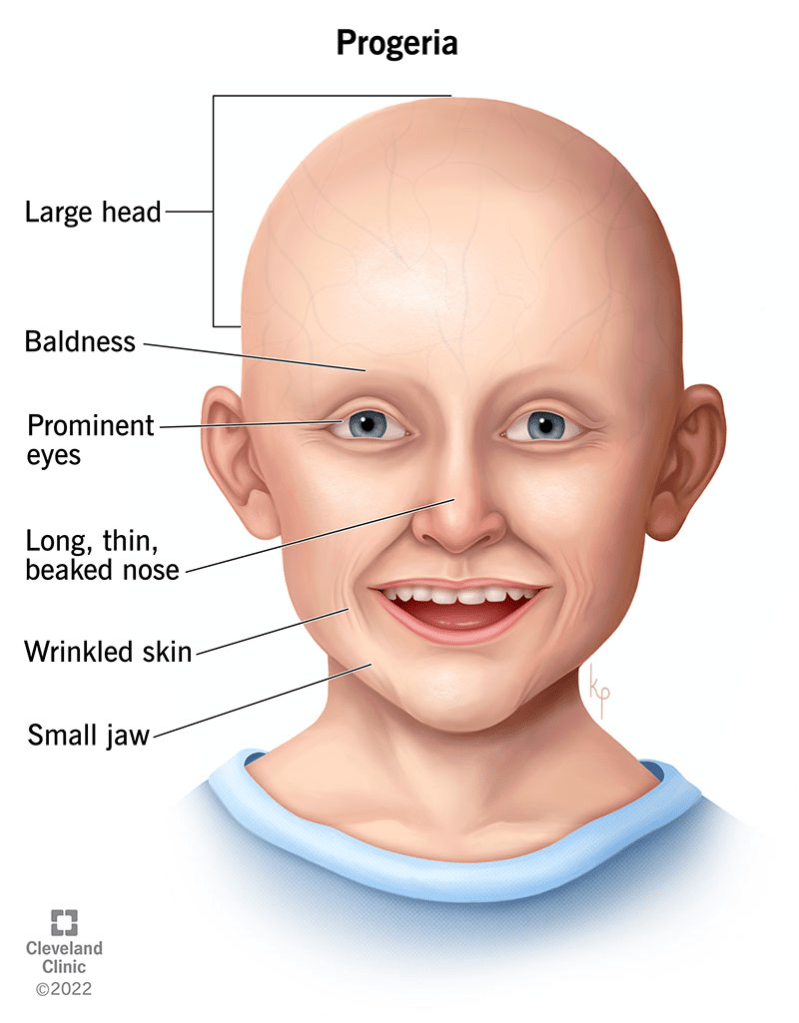

Progeria, also known as Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, is a very rare and fatal genetic disorder that causes children to show signs of rapid aging. Babies with progeria usually look normal at birth, but between nine months and two years old they begin to grow much more slowly than expected, leading to short height and low weight. As the condition progresses, children develop a distinct appearance that includes a small face compared to the size of the head, a small lower jaw, crowded or misshapen teeth, large eyes, a small nose, and a faint bluish tint around the mouth. By around two years of age, they typically lose their hair, eyebrows, and eyelashes, sometimes growing thin, light-colored hairs in their place. Other common symptoms include hardened and narrow arteries, heart disease, strokes, hip problems, visible scalp veins, loss of body fat under the skin, nail defects, stiff joints, and bone issues. These changes cause the arteries to thicken and lose flexibility, leading to serious heart problems at a young age. Most children with progeria die from heart disease at an average age of about fourteen and a half. Like older adults with heart disease, they may suffer from high blood pressure, chest pain, strokes, an enlarged heart, and heart failure.

The disorder is caused by a mutation in the LMNA gene, which produces a protein called lamin A. This protein helps maintain the structure of a cell’s nucleus. In progeria, the defective form of lamin A makes the nucleus unstable, which scientists believe causes cells to age prematurely.

Symptoms:

Newborns with HGPS can have unusual signs at birth. Their skin may look tight, shiny, or hardened on the buttocks, upper legs, and lower belly. Some babies have a bluish color in the middle of the face and a sharply shaped nose. Serious growth problems usually become obvious by about two years of age. These children stay very small and weigh far less than what is typical for their height. A child who is ten years old may be about the size of an average three year old.

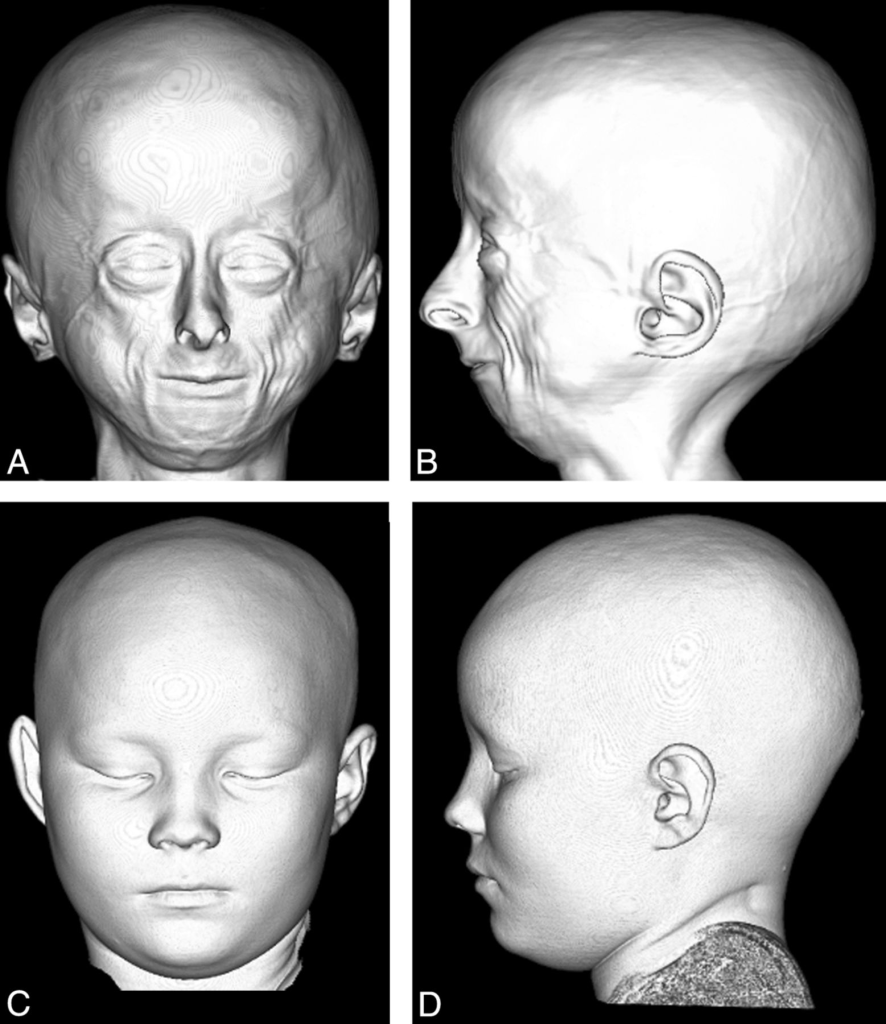

By the second year of life, the bones of the face and lower jaw do not develop fully. The face looks small compared to the head, and the forehead and the sides of the skull may stick out. Children often have other noticeable facial traits such as a small pointed nose, very prominent eyes, small ears without earlobes, and thin lips. Dental problems are common. Teeth may come in late, be irregular, small, discolored, or missing, and tooth decay occurs frequently. The small jaw can also lead to crowded teeth.

Hair on the scalp becomes thin and is usually lost by about age two. Some children grow very fine white or blond hair instead, which may stay for life. Eyebrows and eyelashes may also be lost early in childhood.

HGPS causes clear changes in the skin. As mentioned earlier, some babies have hardened skin in certain areas. As they grow, they gradually lose the layer of fat under the skin. Veins on the scalp and thighs may look very noticeable. The skin takes on an aged look and may become thin, dry, wrinkled, shiny, or tight. Brownish spots may appear on sun exposed areas. Fingernails and toenails may be yellow, thin, brittle, curved, or missing.

Children with HGPS also have unique bone problems. These can include slow closing of the soft spot on the head, a very thin upper skull, and a lack of some air spaces in the skull. They may have short thin collarbones, narrow shoulders, thin ribs, and a narrow chest with a belly that sticks out. The long bones in the arms and legs may be thin and fragile, especially in the upper arms, which can break easily.

Many children develop bone tissue loss in the collarbones, the tips of the fingers, and the hip socket. This can make the fingers look short and narrow. Changes in the hip socket can cause an abnormal hip angle, hip pain, and hip dislocation. Thick fibrous tissue may form around the joints of the hands, feet, knees, elbows, and spine. This leads to stiff joints, limited movement, and joints that look unusually prominent. Because of knee stiffness, hip deformity, and other bone problems, affected children often stand with their legs wide apart and walk with a shuffling motion. They also develop a general loss of bone strength, which causes frequent fractures after even minor injuries.

Other symptoms can include a high pitched voice, missing breasts or nipples, lack of sexual development, hearing loss, and other issues.

Children as young as five may develop severe hardening and thickening of the arteries. This is most noticeable in the arteries that supply blood to the heart and the main artery of the body.

Other heart related problems can appear, such as an enlarged heart and abnormal heart sounds. As children or teens grow, the worsening artery disease may lead to chest pain, blocked blood flow in the brain, heart failure, or heart attacks. These complications can be life threatening during childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood.

Causes:

HGPS happens because of a single letter mistake in a gene on chromosome 1. This gene makes lamin A, a protein that helps form the membrane around the cell’s nucleus. The faulty form of lamin A found in HGPS is called progerin.

HGPS usually does not run in families. The gene change almost always happens by chance and is extremely rare. Other progeroid conditions that are not HGPS can be inherited, but HGPS comes from a new autosomal dominant mutation. It is called sporadic because it is a new change in that family, and dominant because only one changed copy of the gene is enough to cause the condition. For parents who have never had a child with progeria, the chance of having one is about one in four to eight million. For parents who already have a child with progeria, the chance is much higher, about two to three percent. This higher risk happens because of mosaicism. Mosaicism means a parent carries the mutation in a small number of cells but does not have progeria.

The exact reason HGPS causes rapid aging is still unclear. Many scientists believe the rapid aging comes from damage that builds up inside cells over time. During normal chemical processes in the body, certain harmful particles called free radicals are produced. As free radicals build up in tissues, they can damage cells and interfere with how they work, which may lead to aging. The body has special proteins called antioxidant enzymes that help get rid of free radicals. Some researchers think that lower activity of these enzymes may play a role in the fast aging seen in HGPS. In one study, skin cells from children with progeria were compared with skin cells from healthy people. The cells from children with progeria had much lower levels of important antioxidant enzymes, such as glutathione peroxidase and catalase. More research is needed to understand what these findings mean.

Studies have also shown that healthy people make small amounts of progerin, and that it slowly builds up in the coronary arteries as they get older. This supports the idea that progerin contributes to the risk of artery disease in the general population. It may even become a new marker for predicting heart disease. Researchers have confirmed a strong connection among normal aging, heart disease, and progeria. Because of this, finding a cure for progeria could not only help affected children but also help many people who face heart attacks, strokes, and other conditions related to aging.

Diagnosis:

HGPS is most often diagnosed during the second year of life or later, when the signs of early aging become noticeable. Doctors make the diagnosis by doing a full medical exam, looking for the typical physical features, reviewing the child’s medical history, and performing genetic testing. In rare cases, the condition may be suspected at birth if certain unusual signs are present, such as tight shiny skin on the buttocks, thighs, or lower belly, bluish coloring in the middle of the face, or a sharply shaped nose.

Special imaging tests may be used to confirm or better understand bone changes related to the condition. These include looking for loss of bone tissue in the finger bones or the hip socket. Children may also receive detailed heart evaluations and regular monitoring. This can include physical exams, X rays, and specialized heart tests to check for cardiovascular problems and to guide the best treatment plan.

Treatment:

In November 2020, the United States Food and Drug Administration approved Zokinvy, also called lonafarnib, as the first treatment for Hutchinson Gilford progeria syndrome. Zokinvy is a type of drug called a farnesyltransferase inhibitor. It was originally developed for cancer treatment. It is now available by prescription for people with HGPS in the United States, and it can also be accessed in many other countries through Eiger Biopharmaceutical’s Managed Access Program.

Before this approval, children with progeria could only receive Zokinvy by joining a clinical trial run through the Progeria Research Foundation at Boston Children’s Hospital. Since 2007, more than ninety children with progeria have been treated with Zokinvy in four clinical trials.

In April 2018, researchers analyzed data from an observational study supported by the Progeria Research Foundation. They compared children and young adults who took Zokinvy with those who did not. The group who received the drug had a lower death rate. Earlier, in September 2012, the first clinical drug trial for progeria showed that Zokinvy was effective. Every child in that study showed improvement in at least one area, including weight gain, better hearing, improved bone structure, or most importantly, increased flexibility of blood vessels.

Along with Zokinvy, treatment for HGPS focuses on managing each person’s symptoms. Care often requires a team of specialists who plan and coordinate treatment. These may include pediatricians, bone and joint specialists, heart specialists, physical therapists, and other health professionals.

Specific treatments depend on the symptoms. For example, children who have chest pain caused by reduced blood flow to the heart may receive medications that help manage or reduce those episodes.

How You Can Make an Impact:

Without proper research, funding, and support for continued studies and clinical trials to determine possible cures, legitimate medicines for the disease, or preventative treatment, many more children will go on to develop Progeria. If you can, please donate here! If you are unable to donate, consider volunteering your time by raising awareness for this rare disease. If you’re interested in learning more about Progeria, donation opportunities, or the progress being made on potential treatments, visit the Progeria Research Foundation. The Progeria Research Foundation strives “to discover treatments and the cure for Progeria and its aging-related disorders, including heart disease.”

References:

Gordon, A., Gordon, L., & Tuminelli, K. (2021, January 4). Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome – Symptoms, Causes, Treatment | NORD. NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders); NORD. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/hutchinson-gilford-progeria/

Leave a comment