What is ACH?:

Achondroplasia is the most common condition affecting bone growth and occurs in about 1 out of every 20,000 to 30,000 births. It is a genetic condition that causes short stature with an average adult height of around 4 feet. People with achondroplasia often have a larger head, short upper arms, limited elbow movement, distinctive hand shape, and bowed legs. Intelligence is usually normal, and life expectancy is close to average as long as there is no pressure on the brainstem or upper spinal cord where the head and neck meet.

The condition is caused by a change in the FGFR3 gene, which normally helps control how bones grow at cartilage growth areas. This gene change slows bone growth, leading to the physical features seen in achondroplasia. In about 80 percent of cases, the gene change happens spontaneously, while in about 20 percent of cases, it is inherited from a parent.

Symptoms:

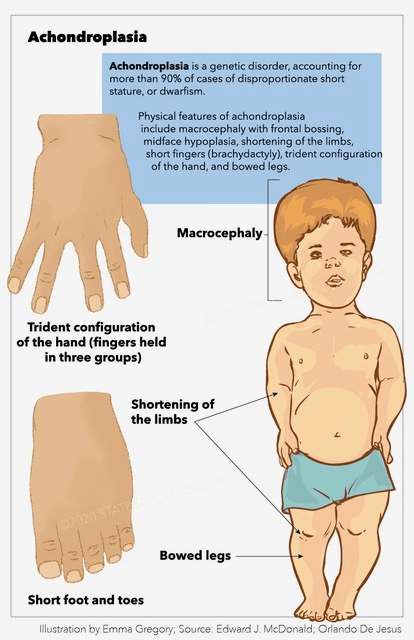

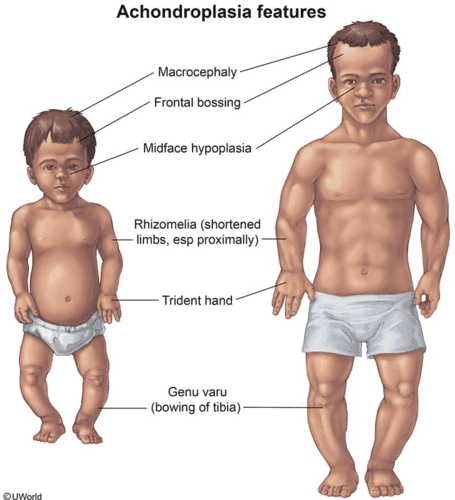

This rare genetic condition causes short stature, usually under 4 feet 6 inches, along with a larger-than-average head, a prominent forehead, and a flattened nasal bridge. The arms and legs are short, and the abdomen and buttocks may appear prominent because of an inward curve of the lower spine. The hands are short, and the fingers often spread into a three-pronged shape when extended.

In infancy, babies typically have a large head with a broad forehead, a flatter midface, a slightly narrow chest, and short arms and legs. About five percent of infants develop a buildup of fluid around the brain that increases pressure. Low muscle tone and loose joints can delay early motor development, such as sitting or walking. Speech, especially expressive language, may also develop more slowly.

Causes:

Achondroplasia is caused by a specific change in the FGFR3 gene, and about 98 percent of people with the condition have the same exact DNA change. In most cases, around 80 percent, there is no family history. These cases happen by chance, and having an older father is thought to increase the risk.

Less often, achondroplasia is inherited from a parent. It follows an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning only one changed copy of the gene is needed to cause the condition. A parent with achondroplasia has a 50 percent chance of passing the condition to a child in each pregnancy, and this risk is the same for both males and females.

Diagnosis:

The physical and imaging features of achondroplasia are well known, and most people with typical signs do not need genetic testing to confirm the diagnosis. However, because medications that support growth in children with achondroplasia are now available, genetic confirmation is often requested. When achondroplasia is suspected in a newborn, X-rays can help support the diagnosis. If the findings are unclear, genetic testing can be used to identify the FGFR3 gene change and confirm the condition.

Common clinical features used to diagnose achondroplasia include short stature with uneven body proportions, a large head with a prominent forehead, a flattened midface and nasal bridge, and shortened arms with extra skin folds. Limited elbow movement, short fingers and toes, hands with a three-pronged appearance, bowed legs, an exaggerated inward curve of the lower spine, and loose joints are also typical signs.

Treatment:

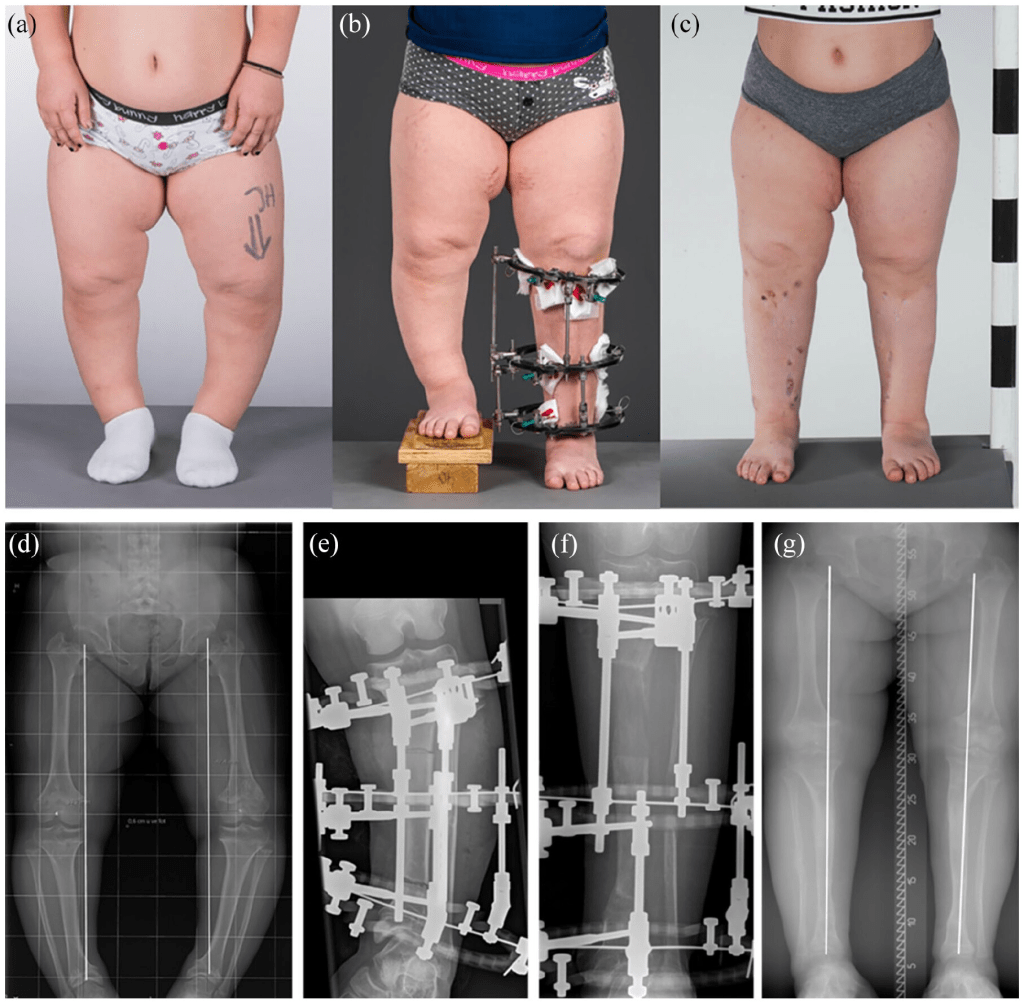

Treatment mainly focuses on managing symptoms. However, new medications that affect bone growth are being developed, and one has already been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Improving bone growth may help reduce some of the health problems linked to achondroplasia.

Vosoritide is a medication approved in 2021 that helps increase height in children with achondroplasia who are at least five years old and still have open growth plates. Research is continuing in younger children to see whether the drug provides other health benefits beyond increased height.

Other treatments being studied include long-acting weekly CNP injections, drugs that block certain growth-related enzymes, antibodies targeting FGFR3, and medications designed specifically to reduce FGFR3 activity.

How You Can Make an Impact:

Without proper research, funding, and support for continued studies and clinical trials to determine possible cures, legitimate medicines for the disease, or preventative treatment, many more children will go on to develop achondroplasia. If you can, please donate here! If you are unable to donate, consider volunteering your time by raising awareness for this rare disease. If you’re interested in learning more about achondroplasia, donation opportunities, or the progress being made on potential treatments, visit Beyond Achondroplasia. Beyond Achondroplasia strives “to inform all people interested in achondroplasia about this rare condition… the right of access to information must be universal.”

References:

Legare, J., Zhou, S., & Pauli, R. M. (2023, November 17). Achondroplasia – Symptoms, Causes, Treatment | NORD. NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders); NORD. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/achondroplasia/

Leave a comment