What is Botulism?:

Botulism is a rare but very serious illness that causes paralysis and is caused by a toxin made by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. It can happen in several ways. People can get it from eating food that already contains the toxin, from spores growing and making toxin in an infected wound, or when spores grow in the intestines. The most common type in the United States affects infants after they swallow spores that then produce toxins in their gut. In rare cases, adults with certain bowel problems can also develop this intestinal form. Botulism has also occurred rarely after medical injections of botulinum toxin used to treat some conditions. Another uncommon type has happened when toxin was breathed in, such as in laboratory accidents, and it could also occur if the toxin were intentionally released. Any case linked to food or with no clear cause is treated as a public health emergency because others could be harmed and because the toxin could be misused as a weapon. For this reason, doctors are required by law to immediately report suspected cases to state and local public health officials.

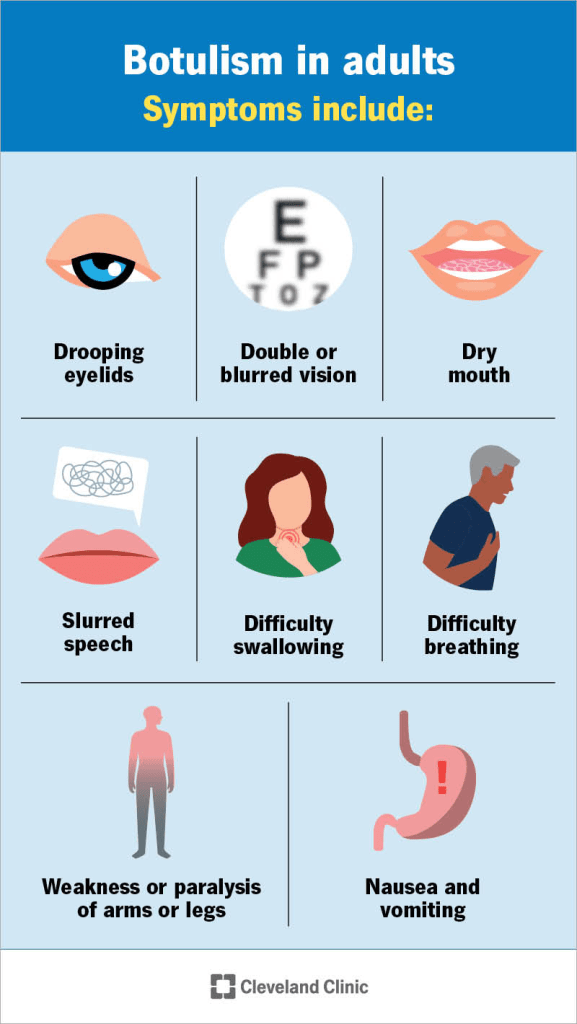

Symptoms:

Foodborne botulism symptoms usually begin within twelve to thirty-six hours after exposure, but they can start as soon as a few hours later or as late as ten days. If botulism is caused by breathing in the toxin, symptoms may appear more quickly. The illness can be mild or very severe. Doctors often recognize botulism by three key features: muscle weakness or paralysis, low muscle tone, and the absence of fever, while the person remains alert and able to think clearly. A fever may develop later if a secondary infection occurs, such as pneumonia from breathing in food or liquid.

The overall course of illness is similar across most types of botulism, including foodborne, wound, and inhalational forms. One difference is that people with foodborne botulism often have stomach and digestive symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea before neurologic symptoms begin.

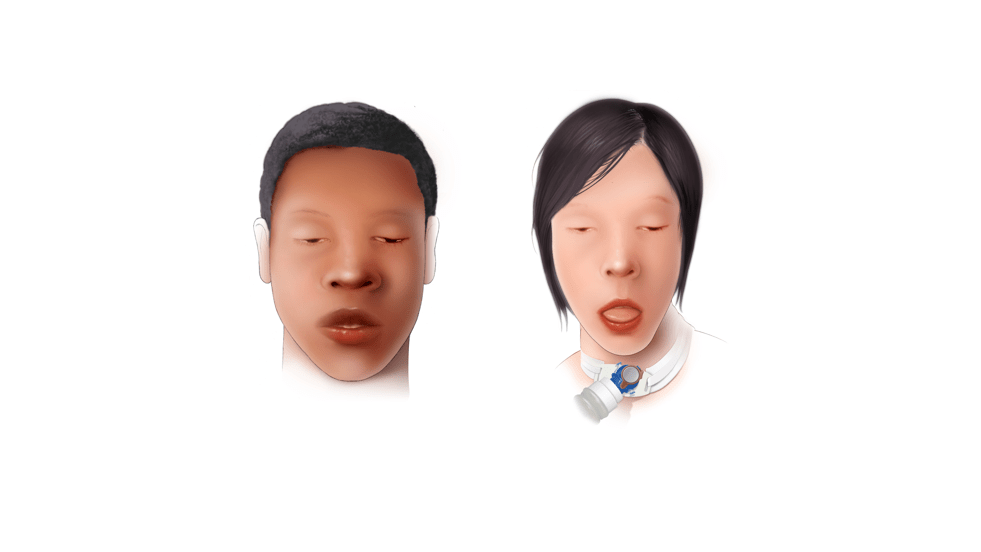

Botulism typically causes paralysis that affects both sides of the body equally and spreads downward. It often starts with the nerves that control the eyes, face, head, and neck, then moves to the shoulders and hips, and later to the hands, wrists, feet, and lower legs. In severe cases, the muscles used for breathing can become paralyzed, which can be life-threatening. Some people also experience stomach pain, constipation, blockage of the intestines, or trouble emptying the bladder. Changes in sensation are uncommon, and thinking and awareness usually stay normal as long as the person is getting enough oxygen.

Problems with the cranial nerves usually appear early and often affect both sides of the body. Eye-related symptoms may include double or blurry vision, trouble moving the eyes, drooping eyelids, enlarged pupils, and poor reaction of the pupils to light. Other symptoms can include difficulty speaking, slurred speech, trouble swallowing, and an extremely dry mouth or throat. The tongue may look swollen or coated because of dryness, and the gag reflex may be weak or absent.

Muscle weakness often spreads quickly from the head down to the neck, arms, chest, and legs. The weakness is usually the same on both sides and moves from larger muscles closer to the body to smaller muscles farther away. Reflexes may be reduced or completely absent. Breathing problems can occur and may worsen into respiratory failure due to paralysis of the throat muscles, diaphragm, and other muscles involved in breathing.

Wound botulism causes the same nerve-related symptoms as foodborne botulism, but stomach symptoms are usually not present, and no contaminated food is involved. Careful examination of the skin is important to look for wounds. In the United States, wound botulism most often affects people who inject drugs, especially black tar heroin, and it is reported most commonly in western states. It can also rarely happen after injuries contaminated with soil or after surgery. Fever may be present if there is another bacterial infection.

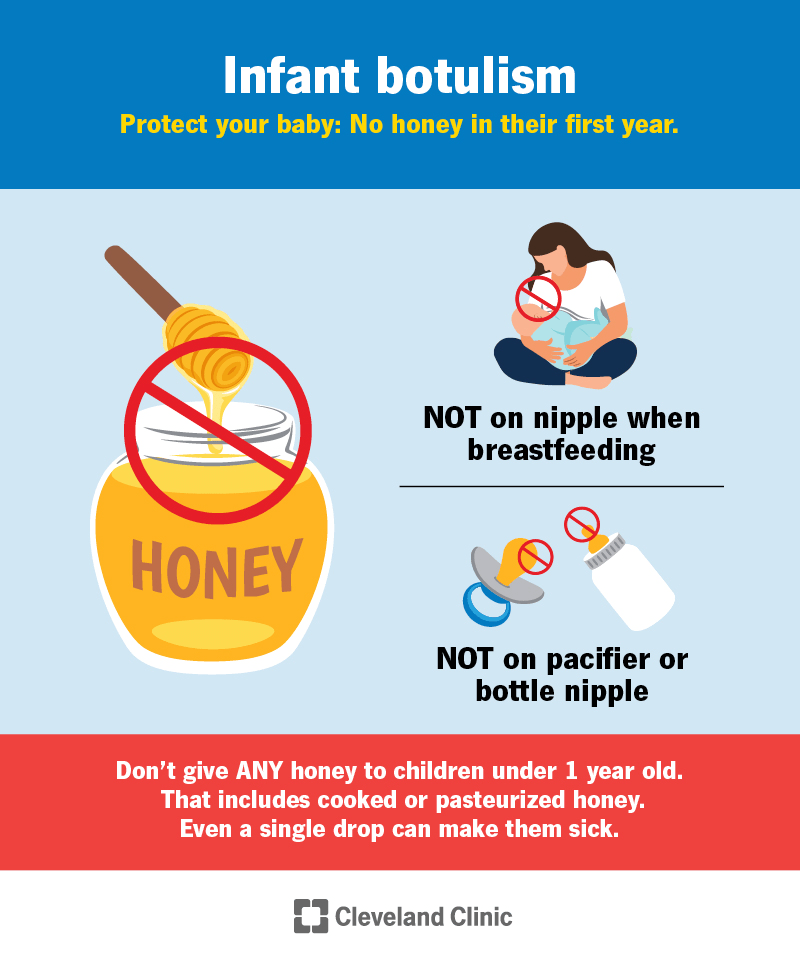

Infant botulism usually affects babies younger than one year old. The toxin causes constipation, weakness, poor sucking and swallowing, a weak cry, loss of muscle tone, and eventually limp paralysis. The severity and speed of onset can vary widely among infants. When there are no complications, infants fully recover.

Causes:

Foodborne botulism happens when a person eats food that already contains toxin made by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. Wound botulism occurs when this bacterium infects a wound and produces toxin there. Infant botulism and the rare adult intestinal form are different because they happen after swallowing bacterial spores. These spores grow inside the large intestine and then release toxins. Honey is the only known food that clearly contains these spores and can be avoided in infants. Even after testing many foods and objects that babies commonly put in their mouths, most cases of infant botulism still have no clear source. It is believed that spores may often come from tiny particles of dust that are swallowed.

Botulinum toxin causes muscle weakness and loss of muscle tone because it blocks the signals between nerves and muscles, preventing muscles from contracting.

Clostridium botulinum is found naturally in soil and in ocean and lake sediments around the world. In the United States, foodborne botulism has most often been linked to home-canned foods, especially vegetables, and to traditional Alaska Native foods, particularly fermented fish.

The bacterium can produce seven different types of toxin, labeled A through G. In humans, botulism is most commonly caused by toxin types A, B, and E, and rarely by type F. Most foodborne cases come from contaminated home-canned foods, but outbreaks have also been linked to commercial or restaurant foods and unsafe food handling. Botulism has also been associated with baked potatoes kept in aluminum foil at room temperature, as well as garlic or onions stored in oil. Illegally made alcohol in prisons, sometimes called hooch or pruno, has also caused outbreaks. Type E botulism is usually connected to eating preserved, uncooked fish or other aquatic animals. Types A and B are the main causes of infant botulism and wound botulism.

Diagnosis:

Botulism can often be diagnosed by doctors using a careful physical exam and a detailed review of the patient’s symptoms and medical history. Laboratory testing is used to confirm the diagnosis. The most reliable tests include the mouse bioassay and mass spectrometry-based methods such as Endopep MS. These tests can detect botulinum toxin in blood, stomach contents, stool, or suspected foods in cases linked to food exposure. Botulism can also be confirmed by growing Clostridium botulinum bacteria from samples taken from the stomach, stool, or an infected wound in cases of wound botulism.

Treatment:

Foods that are canned at home or bought from stores must be prepared, stored, and handled correctly to prevent botulism. Any food that looks spoiled should be thrown away. Cooked foods like soups and stews should be refrigerated right away. Store-bought foods should also be refrigerated if the label says to do so.

The bacteria that cause botulism can survive normal cooking temperatures for a long time. Very high heat is needed to destroy the spores. The toxin itself is easier to destroy and can be made harmless by thoroughly heating food or boiling it. Home-canned foods are the most common source of botulism, but store-bought foods have also caused cases. Foods often involved include vegetables, fish, and condiments, but meat, dairy, and poultry can also be affected. Infants under one year old should not be given honey because it can lead to infant botulism.

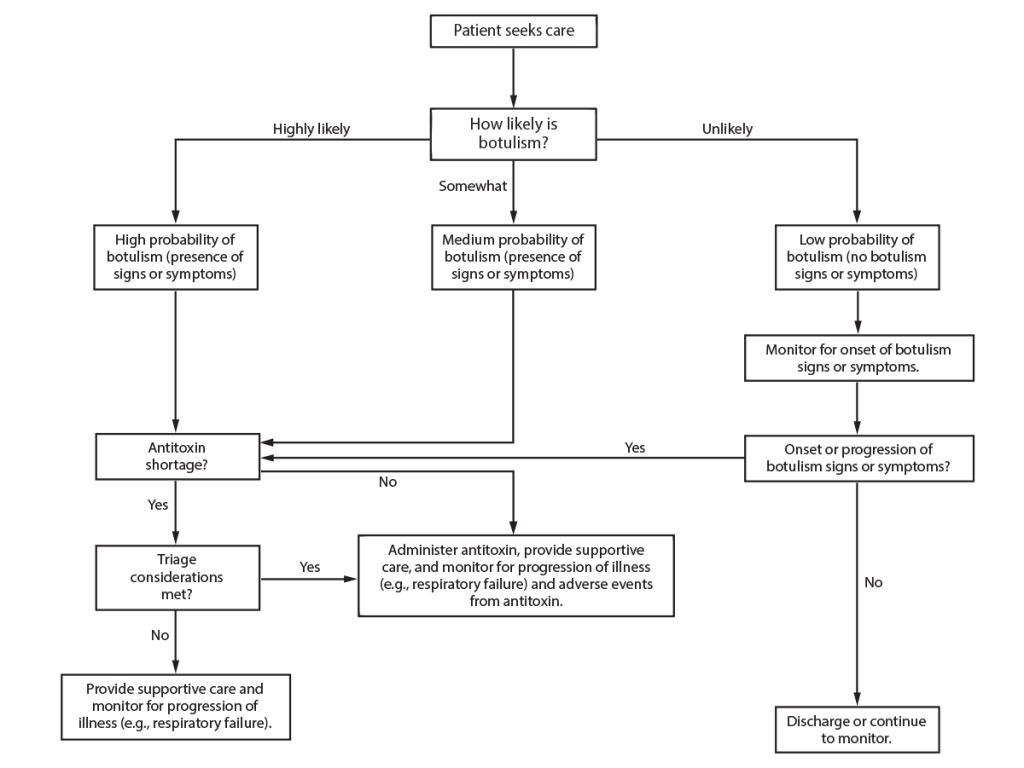

Botulism is a medical emergency because it can cause serious breathing problems. People with suspected botulism need to be hospitalized and treated quickly with antitoxin. Doctors should immediately contact local or state health departments if they suspect botulism so testing and treatment can begin as soon as possible. Early reporting also helps prevent additional cases. Health departments and the CDC are available at all times to respond.

Supportive care, including breathing machines when needed, can save lives. Antitoxin works best when given early and can stop the illness from getting worse, but it cannot reverse nerve damage that has already occurred. Recovery takes time because nerves must heal on their own. A special antitoxin that works against all known types is available through the CDC, and treatment should begin as soon as botulism is suspected if the benefits outweigh the risks.

For infants with botulism, a special treatment called BabyBIG is available and can greatly shorten hospital stays if given early. Doctors should first contact their state health department and then request the treatment through the Infant Botulism Treatment and Prevention Program.

Antibiotics are usually not used to treat botulism. If antibiotics are needed for another infection, certain types should be avoided because they can make muscle weakness worse. Older treatments such as guanidine are no longer used.

How You Can Make an Impact:

Without proper research, funding, and support for continued studies and clinical trials to determine possible cures, legitimate medicines for the disease, or preventative treatment, many more children will go on to develop botulism. Consider volunteering your time by raising awareness for this rare disease. If you’re interested in learning more about botulism or the progress being made on potential treatments, visit the Infant Botulism Treatment and Prevention Program.

References:

Edwards, L. (2023, July 26). Botulism – Symptoms, Causes, Treatment | NORD. NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders); NORD. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/botulism/

Leave a comment